When the industry regulator later releases specifics of its price cap, the debate over government assistance with household energy bills will heat up.

Because the price of gas and electricity is capped by a government guarantee, Ofgem's announcement will have no impact on how much consumers pay per unit.

But it's likely to show that the cost of support to the government is less than was first thought.

Campaigners argue that ministers should prevent an increase in energy prices in April.

The government did not have the "headroom to make a major new initiative to help people," according to Chancellor Jeremy Hunt, who previously told the BBC that the policy was still being reviewed.

Under the government's Energy Price Guarantee (EPG), a household in England, Wales, and Scotland using a typical amount of gas and electricity currently pays £2,500 a year for energy. That annual bill would have been £4,279 without government assistance since January.

The EPG will be less generous starting in April, according to the chancellor, meaning the average household will pay £3,000 annually.

What that bill would have been without the guarantee from April to July will be revealed by Ofgem later on Monday. Because wholesale prices have decreased, analysts at consultancy firm Cornwall Insight estimate that to be £3,295.

The difference between the guarantee and the cap set by Ofgem is paid to energy suppliers by the government.

The EPG got going in October of last year and is supposed to last until April of 2024. Despite being billions of pounds less than initially estimated due to declining wholesale prices, the potential cost to the government would still come to just under £30 billion.

Such numbers were and still might be very erratic. According to the government, rather than a pool of money that could be used elsewhere, the "savings" would be money that wasn't borrowed. The government has been urged to change its mind about raising the average annual bill from £2,500 to £3,000 in April as a result of the figures, according to dozens of charities and campaigners.

The bill increase was called a "national act of harm" by consumer finance expert Martin Lewis. The same call has been issued by both Labour and the Trades Union Congress (TUC).

"At the Budget meeting next month, the government must postpone the impending increase in household energy costs. Sky-high bills are driving families to the breaking point across Britain, according to TUC general secretary Paul Nowak.

The Liberal Democrats have taken it a step further and advocate for lower energy costs.

Suppliers must notify customers in writing one month prior to a price increase, so letters will be delivered this week, two weeks before the Budget.

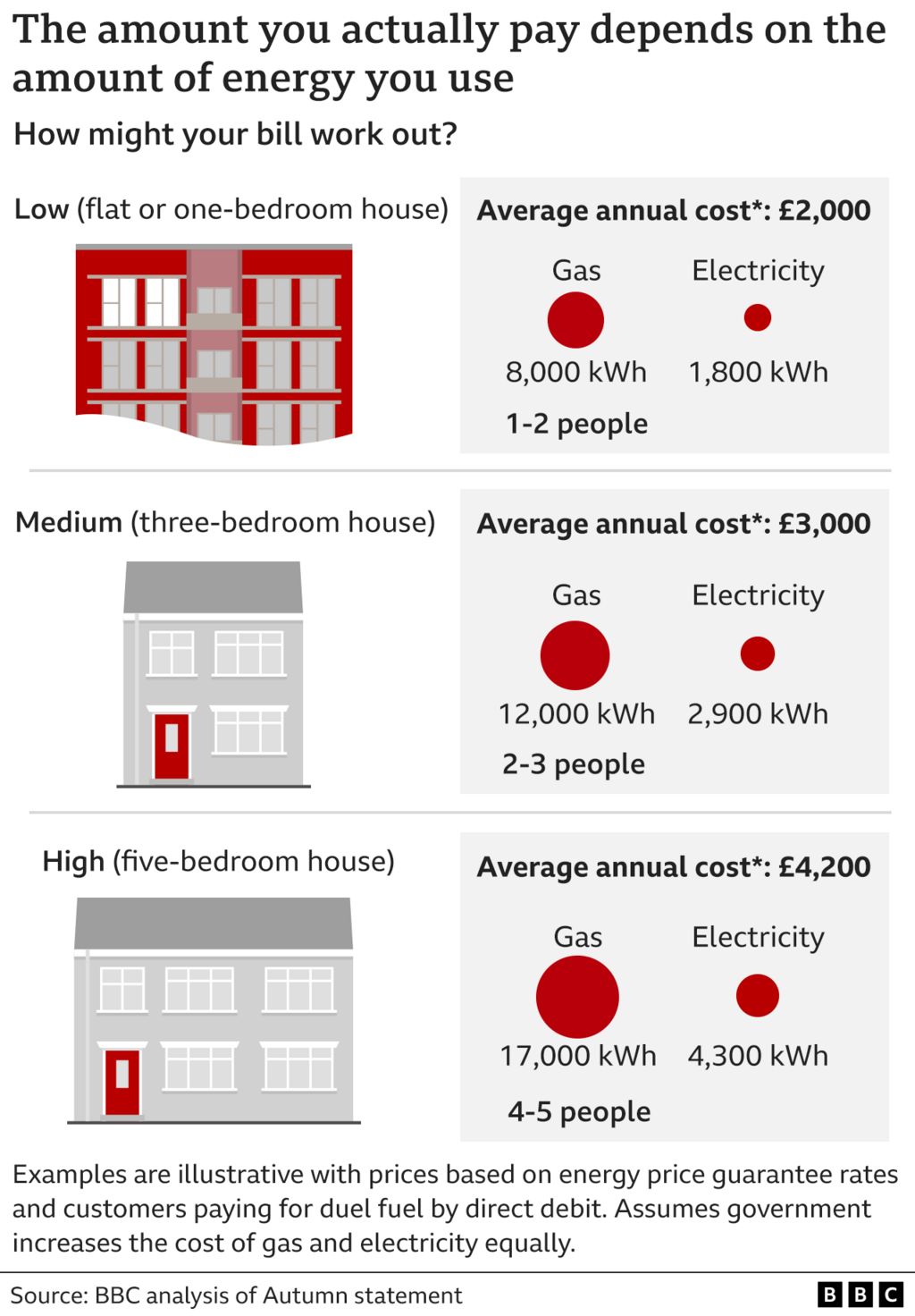

The government guarantee does not place a cap on the overall cost, just like any energy price cap. The price per unit of energy is constrained.

This is demonstrated by displaying the annual bill for a household using the average amount of gas and electricity, which is expected to be £3,000 in April. A renter who lives in a small, well-insulated apartment will use less energy and spend less money. Pay more if you live in a big, drafty house.

With six monthly discounts on bills of about £67, the government reduced everyone's bills by an additional £400 this winter. However, this support ends in April. In Northern Ireland, where the market is more complicated and many households use heating oil, lump sum payments are also an option.

Households in the UK with low incomes and benefits, as well as retirees and people with disabilities, will continue to receive cost-of-living payments, which can be worth hundreds of pounds.

Despite the backing, the nonprofit National Energy Action predicts that 1.5 million more households will experience fuel poverty as a result of the bill increases in April, which refers to situations where a household spends more than 10% of its income on energy.

Households will receive an update on their standing charge payments in Ofgem's announcement later. For a gas and electricity connection to your home, you must pay these fixed daily rates.

These fees might increase if previously agreed-upon rules for electricity transmission are changed. These currently fall outside of the scope of the government's guarantee, which could result in a further, albeit minor, rise in people's bills. These differ by region, so your location will also affect the price.

Separately, people who currently pay their energy bills in cash or by check upon receipt of a bill typically pay about £250 more annually than those who pay by direct debit each month. In the past, Ofgem has claimed that these customers incurred higher costs from suppliers because they were more likely to be late with payments.

Due to higher fixed costs, top-up prepayment meter customers' annual bills are £55 higher than those of typical direct debit customers.

Ofgem is anticipated to update the numbers later on the variation in bills between the different forms of payment.

Due to declining wholesale prices, predictions indicate that household bills will drop below the government guarantee by July and once again be subject to Ofgem's cap.

This would also reduce the amount of windfall taxes paid to the government.

Additionally, it might lead to a resurgence of competition among suppliers of fixed prices for households.

However, Jonathan Brearley, the CEO of Ofgem, cautioned customers to proceed with caution and "do your homework" regarding how prices may change in the future before making a decision.