Prices in the thriving sports memorabilia market don't appear to be slowing down. But how can collectors who shell out thousands, or even millions, of pounds know they are getting the real deal?

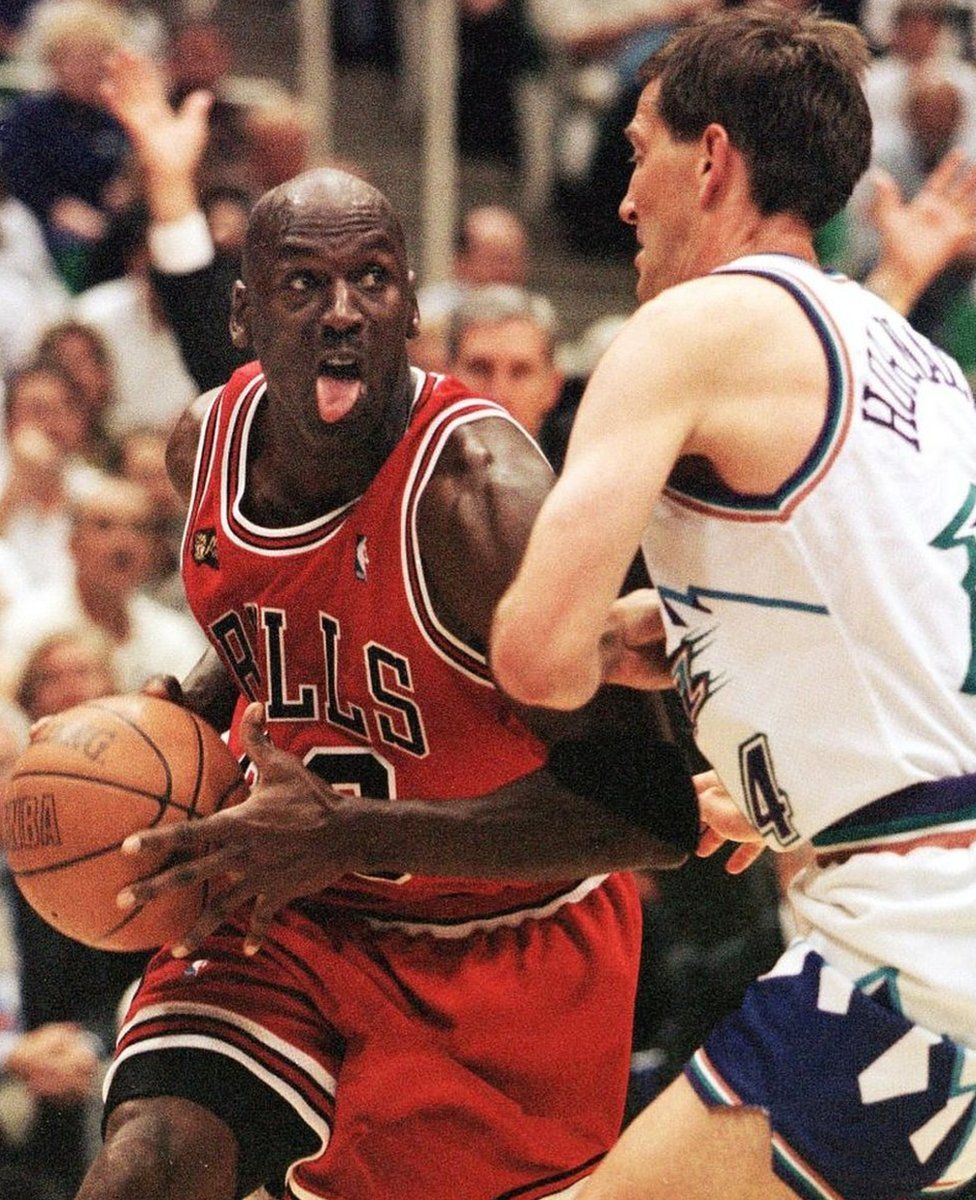

When Michael Jordan's No. 23 was hit with a hammer, The $10.1m (£8.8m) price for the number 23 jersey from the first game of the 1998 NBA Finals made headlines around the world.

A world record for a piece of match-worn memorabilia was set by twenty bidders who were motivated by the desire to own what the auctioneers called "a rarefied piece of history.".

The amount soared higher than the previous record of £7.9 million, which Diego Maradona's infamous "Hand of God" football shirt had previously set just a few months earlier.

Even though very few people would ever consider competing for those specific items, the market as a whole continues to thrive with thousands of pieces of gear traded each year by auction houses, specialized websites, and private collectors.

But how straightforward is it to establish that a shirt or set of boots belonged to a specific player months, years, or even decades later? What happens when ownership of an item is disputed?

When Scotland defeated the reigning world champions England at Wembley in 1967, a shirt allegedly worn by footballer Jim Baxter was withdrawn from auction by Glasgow auction house McTear's after two other parties asserted that jerseys they own are in fact authentic.

In addition, Maradona's family tried to stop the sale of the Hand of God shirt last year by claiming the star had been wearing a different shirt in the second half of Argentina's 1986 World Cup quarterfinal, also against England, when he scored two of the tournament's most illustrious goals.

According to Sotheby's, the item's "remarkable provenance"—a record of its lineage—proved that assertion to be false.

The jersey was displayed at the National Football Museum for almost 20 years after it was exchanged with England midfielder Steve Hodge. Both players had written detailed accounts of the exchange in subsequent books.

By analyzing distinctive details like patches, stripes, and numbering, photo-matching experts were also able to produce "conclusive" results.

An additional level of confirmation was provided by the chief scientist at Sotheby's, according to a spokeswoman.

According to David Convery, head of sporting memorabilia at Graham Budd Auctions in Northamptonshire, trying to piece together an item's history is frequently a "minefield.".

As we go through the verification process, there are many techniques we use as specialists—small details the general public might not be aware of.

"The most difficult task is to prove it. But in the majority of cases, we start with the vendor. Is it a family member or an ex-player?

Convery says there are times when help is enlisted from private collectors who specialize in a particular area, despite having decades of experience and working at Christie's where he helped sell Pele's Brazil shirt from the second half of the 1970 World Cup final for almost £160,000.

Overall, such research results in "hundreds and hundreds of items" being rejected each week because they didn't pass the business's verification checks.

According to his colleague Adam Gascoigne, CEO of Graham Budd, "one thing I've certainly learned is not to take anyone's word.".

Details are lost in the mists of time, but it may not always be someone trying to fake something.

In the 1970s and 1980s, when there wasn't much of a memorabilia market and people weren't as aware of what they owned or where they kept it afterward, there were many instances of players [mistakenly] believing that a shirt they wore in a specific game is what they are thinking about. ".

Transparency is important to Gascoigne. Although he advises bidders to always read listings carefully and conduct additional research, he believes that bidders should feel secure in the actions that respectable companies take.

"We're obviously trying to describe something accurately, and if we can't show that it's a match shirt, we won't say that it is," the author said.

"Errors happen when working with hundreds or thousands of lots. Generally, we'll pick them up before the auction, but occasionally something will come up.

"Where values rise, there is obviously a greater temptation to fake things, especially with autographs. How many forged Muhammad Ali signatures there were in the 1990s and 2000s is well known.

The actual items are more challenging. We should, in my opinion, constantly be on guard.

"Considering how many lots must be sold each year, I don't believe [issues with auction houses are particularly common. Additionally, a lot of transactions take place privately and on websites like eBay. It's a bit of a gray area there.

"I can only speak from our point of view. It is best to remove an item from consideration if there is any doubt until the matter is clear. ".

An example of this happened last year when the company withdrew a shirt that was purportedly worn by Sergio Aguero when he scored his infamous injury-time winner on the final day of the season to give Manchester City the 2011–12 Premier League title.

It was expected to bring in more than £30,000 when Neville Evans, one of the nation's top football memorabilia collectors, put it up for auction to benefit cancer and stroke charities.

The decision's justifications have not been made public.

Gascoigne says, "That one is really hard to comment on.". "I think the best thing I can say is that after new information became available, it was preferable to remove the item.

"There was a great deal of disappointment, and it's too bad it came to that, but you can only deal with the information as it comes to you.

"[Neville's] collection is amazing. He is a dependable customer and lends memorabilia to the National Football Museum. When people of that stature own something, it's a significant possession. Not just someone you've never heard of is involved. ".

The shirt was later put on the market by another auction house before being taken off the market once more in October.

A request for comment from Mr. Evans was ignored.

Any skepticism about the larger market, according to Convery, would ultimately harm companies' reputations and — because they take commission — their bottom lines.

"It's incredible to see these objects. I'm probably the only Scotsman to have kept nine of the 11 medals [originally] awarded to the 1966 England team, in addition to a medal from every World Cup tournament.

"We want to ensure that everything is as accurate as it can be so that customers can buy with confidence.

"People need to get it right with such high values. Sure enough, that.

. "