On Wednesday, the NHS will turn 75, but the momentous occasion has been met with dire predictions that it won't make it to its 100th birthday without significant change. The answer, according to experts, ranges from sin taxes to cutting back on care for the terminally ill.

Short-term treatment for injuries and infections was the primary focus when the NHS was established, but the challenge today is very different.

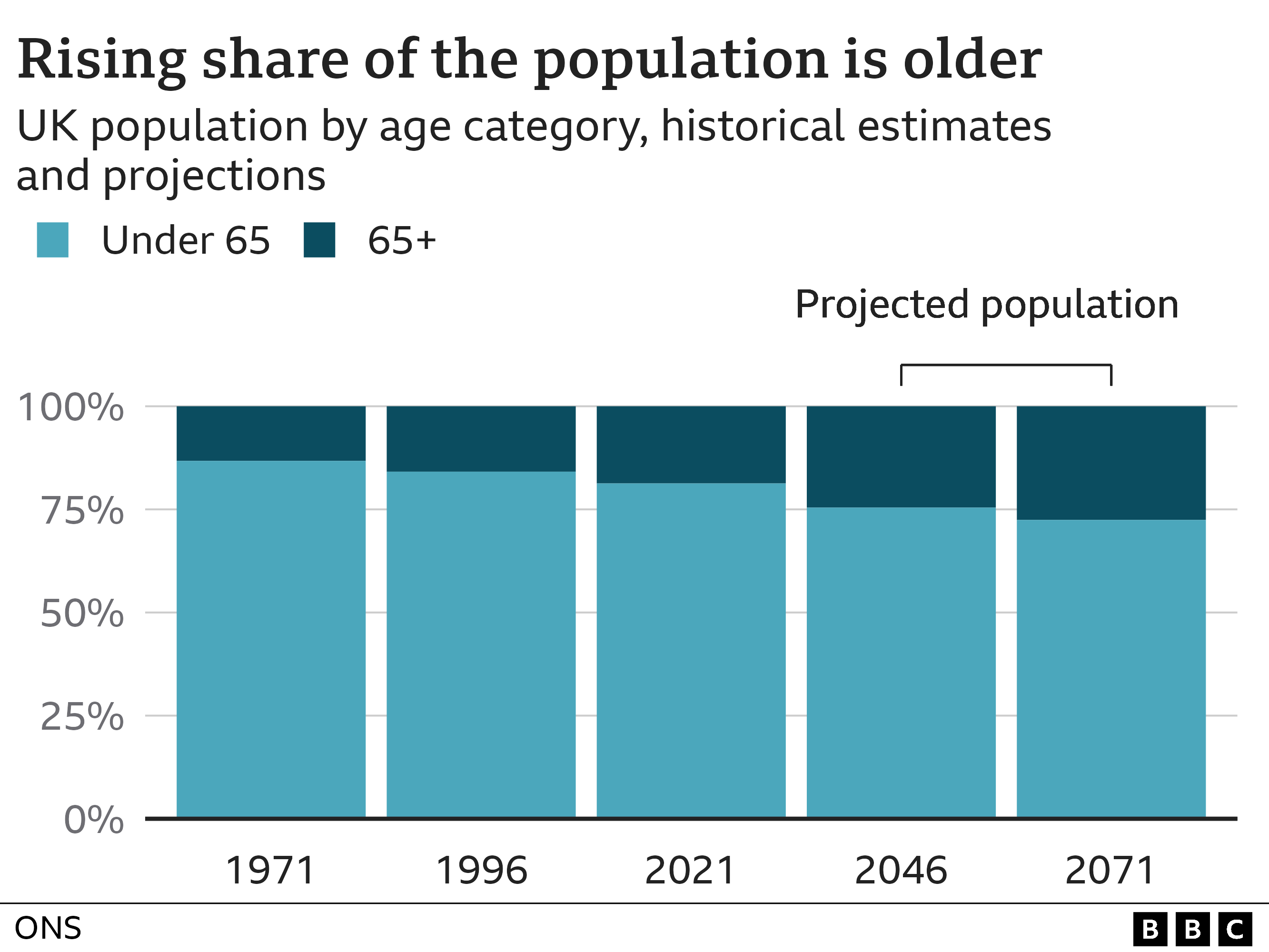

Numerous people are living with chronic health conditions that require long-term care and have no known cure, such as diabetes, dementia, and heart disease, as a result of the aging population.

According to current estimates, the NHS spends about £7 of every £10 on patients with these conditions. The majority of people over 65 have two or more.

And things will only get worse from here. Anita Charlesworth, director of research and economics at the Health Foundation, predicts an increase in the numbers. The baby-boom generation is getting older.

"Their health will be shaped by the lives they have led, and they come from a generation that has seen the rise in obesity firsthand. Their poor health is ingrained. The next twenty years will be very difficult. ".

It will be necessary to increase funding for the NHS, but this must be done in conjunction with a change in how resources are allocated, so that more money is spent "upstream" in the community on things like social care, which is provided outside of the NHS, and prevention, which enables people to better manage their conditions without needing hospital care.

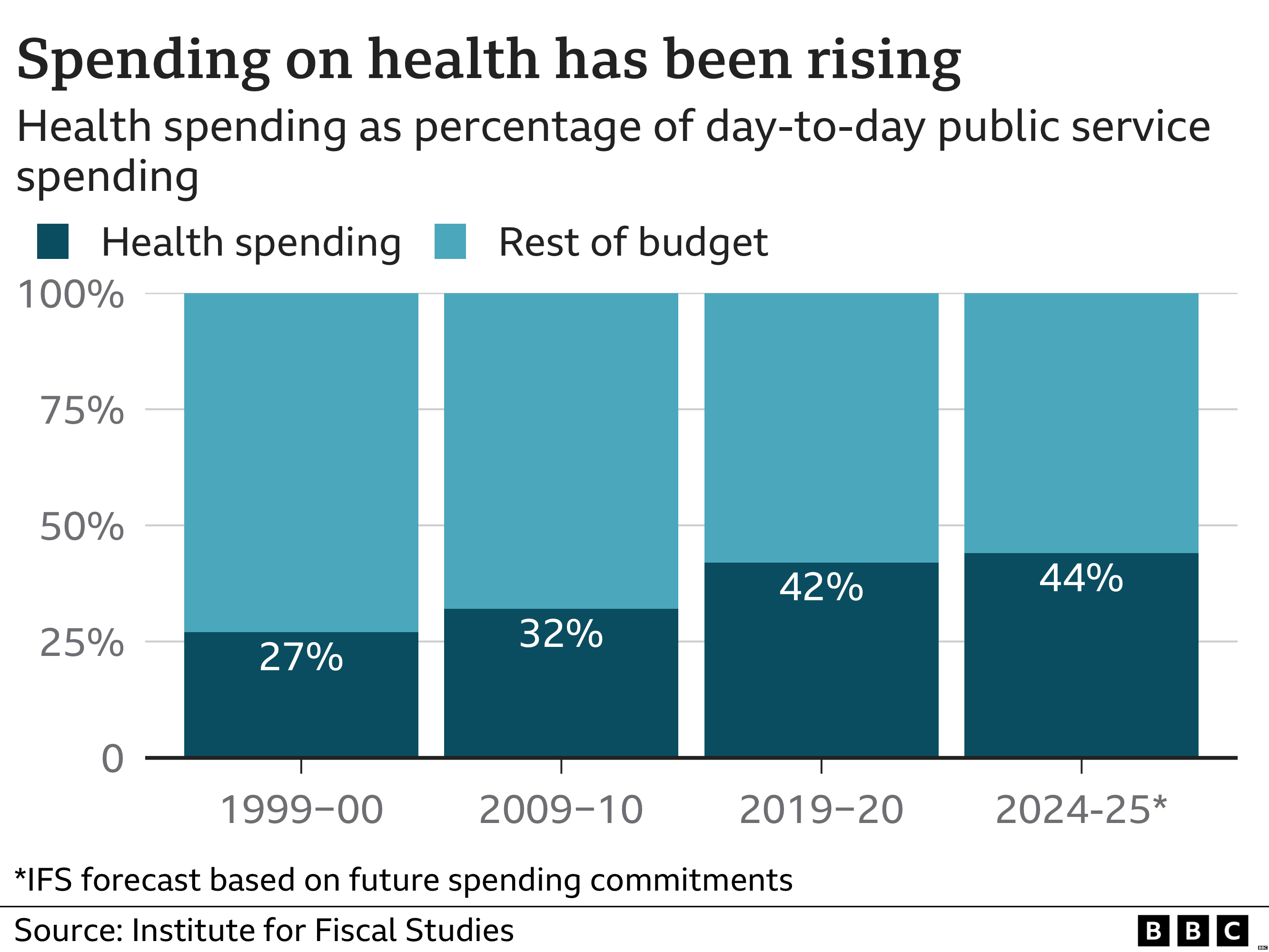

Many people are questioning whether such spending is sustainable, however, given that the amount of public money spent on the NHS has increased ever since the health service was established – it now represents more than 40p of every £1 spent on regular public services, once things like welfare are excluded.

The NHS should be open to adopting strategies used by other nations, according to former health secretary Sajid Javid, who has proposed charging for GP visits and called the current course of action "unsustainable.".

However, Ms. Charlesworth, who formerly served as the Treasury's director of public spending, asserts that additional funding can be found and notes that other nations must make similar sacrifices.

She claims that this is not specific to the UK or our system. "It is a worldwide occurrence. However, increasing funding for the NHS will require economic expansion; otherwise, other services would have to be cut or taxes would have to be raised. ".

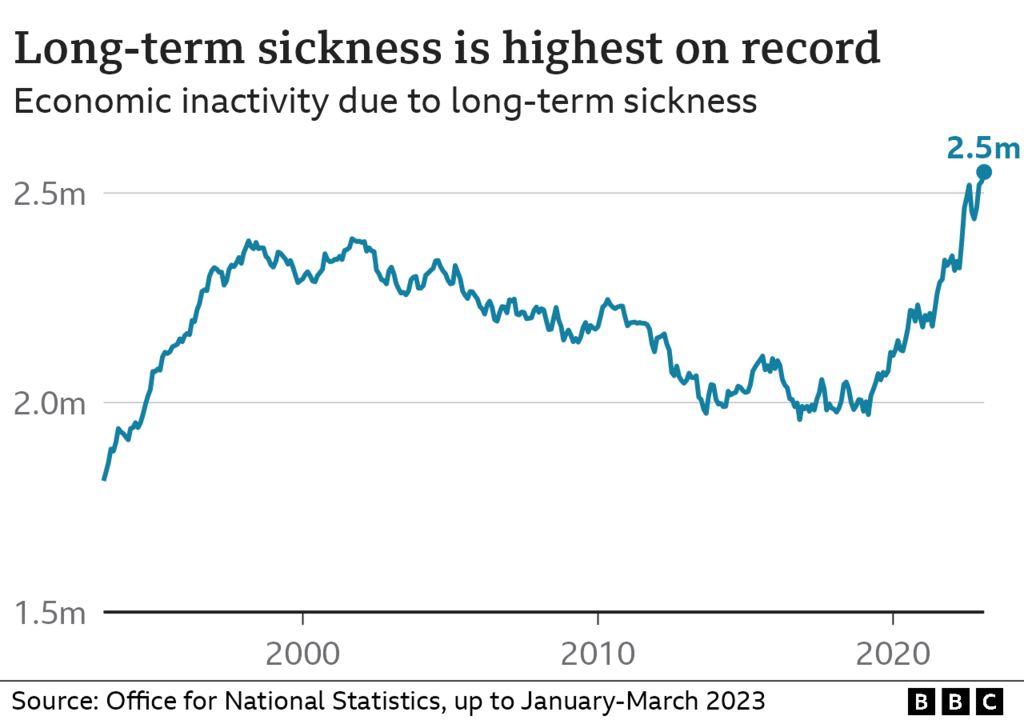

Ms. Charlesworth argues that healthcare spending should be viewed as an investment in the nation rather than a cost, citing statistics showing that 21.5 million people are out of work due to poor health, or one person out on long-term sick leave for every 13 people employed.

Economic growth is dependent on good health, but there are currently too many people on waiting lists, and there is a problem with mental health in particular. " .

Siva Anandaciva, the chief policy analyst at the King's Fund, recently produced a report for the think tank comparing the NHS to other wealthy countries. He says the increase in workforce announced by the government last week will take years to have an impact on the immediate issues with the backlog and aging infrastructure.

In comparison to many other comparable countries, the NHS had fewer employees and less equipment, such as scanners, according to his report. To those who suggested a different funding model might be necessary, he made it clear that the findings were not an argument for switching to a different system and added that there was little evidence that any one particular approach was inherently superior to another.

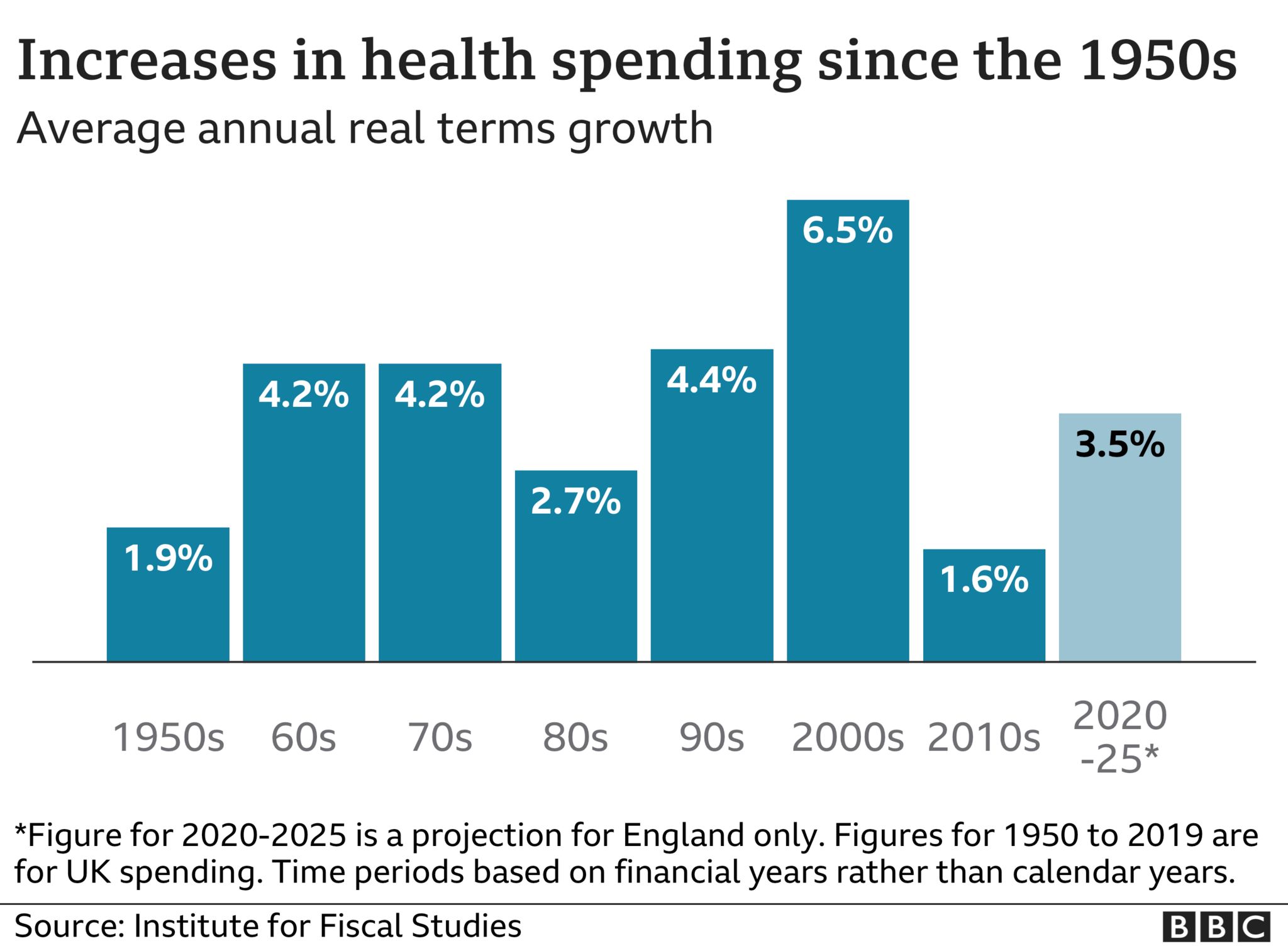

According to Mr. Anandaciva, "History shows us that we do need to spend more on the NHS.". "Anything less than 2 percent is managed decline, and the 3 to 4 percent we are currently spending is just stagnant. ".

That will probably require allocating a larger portion of public funds to the NHS, he says, but digital technology can reduce spending in other areas because the NHS relies so heavily on labor. You will eventually require a nurse to administer care, he continues.

Since the establishment of the NHS, life expectancy has increased, but healthy life expectancy has not kept pace; as a result, the average person can now expect to spend more than 20 years in poor health, according to the Office for National Statistics.

According to Mr. Anandaciva, "We had hoped that medical advancements would lead to people living longer and living longer in good health, but that has not happened.". It will necessitate that we become much healthier and more active. ".

He asserts that the NHS has little control over many of the variables that affect how people live. These so-called social determinants include neighborhood, housing, employment, and education.

Mr. Anandaciva supports the use of "sin taxes" such as minimum alcohol pricing and levies on sugar and salt to influence behavior and would like to see employers in particular take a greater interest in the health of their workforce.

But he adds that an open discussion about how to prioritize that spending will also be necessary. According to Mr. Anandaciva, "At the end of life, our use of healthcare increases and costs more.". Would money be better spent in another area?

Prof. Sir David Haslam, who formerly served as chair of the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence, which determines which treatments should be made available on the NHS, also makes this point.

Sir David, who wrote the book Side Effects about the difficulties the NHS faces, believes there should be a greater emphasis on getting the "most for our money.".

He claims that there is an excessive amount of attention paid to medications and treatments that merely prolong life as opposed to programs that help people live in good health.

According to research, having the same general practitioner for many years significantly lowers the likelihood of hospital admission, says Sir David. If that were a medication, we would laud it as a miracle cure, but instead, we've seen the number of GPs decline. ".

He claims that the medical field as a whole is too "super-specialised" and calls for more generalists to treat "the individual rather than their organs" in the community and hospitals.

Patients with six or seven conditions may spend all of their time visiting various hospital departments and seeing various specialists, frequently with poor coordination between them, according to Sir David.

He also raises concerns about how much medical assistance is given to dying patients.

According to Sir David, "too many frail elderly patients are dying in hospitals when that may be completely inappropriate.".

"We have medicalized death too much. When I pass away, I want to do so in my house while receiving top-notch care. This is about giving rational care, not about rationing it.

. "