Millions of people who survived Myanmar's most powerful cyclone are now battling to rebuild their lives after the government barred aid organizations from entering the affected areas.

Human Rights Watch has claimed that the action has "turned an extreme weather event into a man-made catastrophe.".

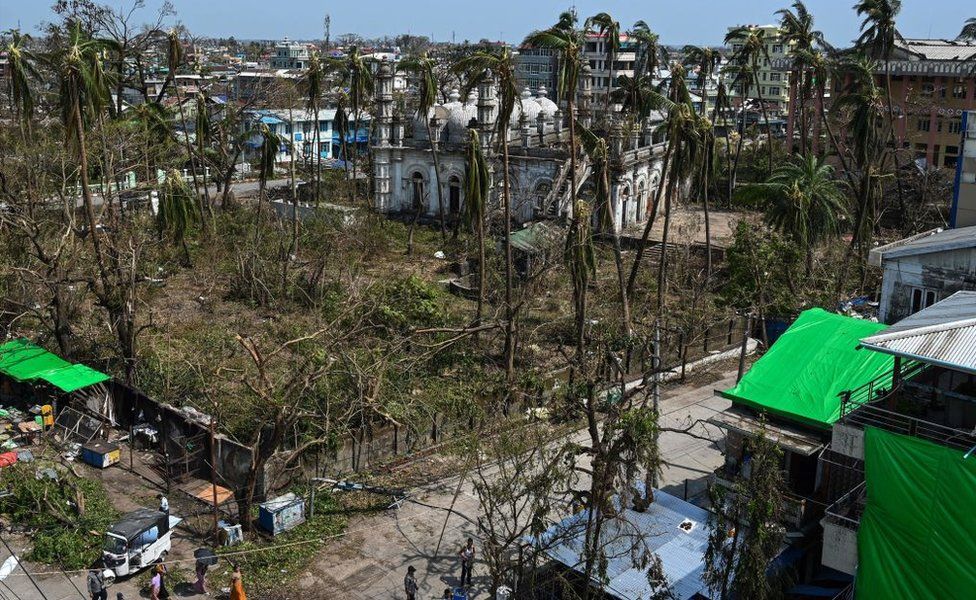

Hundreds of people were killed when Cyclone Mocha struck on May 14.

A month after their homes were destroyed, the BBC spoke to families who are in shock over the diminishing aid. .

According to Aye Kyawt Phyu, who resides in Sittwe, the capital of the severely damaged Rakhine state, there is not enough food or water, and finding either has become much more difficult now that the monsoon season has begun. The week has been cloudy. Every day is difficult for us. The school where the kids go to school has no roof. " .

"All the houses fell when the storm hit.". San San Htay, a resident of Sittwe, stated that there is nowhere to stay. "I am currently sitting in the rain when it rains. Even sleeping is difficult for me. " .

According to the UN's humanitarian office, only a small percentage of damaged homes have been repaired. The covert National Unity Government calculates that the death toll was closer to 500 than the junta, which claims that the cyclone claimed 145 lives. Over 2,000 villages and 280,000 homes were reportedly destroyed by the storm, according to the Arakan Army, an ethnic insurgent group in Rakhine.

Nearly 3.2 million of the 5.4 million people in Myanmar who were in Cyclone Mocha's path are deemed to be among the "most vulnerable," according to the UN. Aye Kyawt Phyu and San San Htay reside in Rakhine, one of the poorest states in the nation. In 2019, 78 percent of its people were estimated to be living below the poverty line by the World Bank.

Aye Kyawt Phyu declares, "We want the government of Myanmar to permit outside aid.". She claims that they received some rice, clean water, and oil in the days right after the storm.

Up until 8 June, when the military junta in charge of Myanmar forbade aid organizations operating in the region from using their vehicles, aid continued to trickle in but could no longer be delivered.

Why they did this was never given by officials. However, a Rakhine government spokesman told the local media that they wanted to oversee the distribution of aid, which they felt had not been done fairly.

According to him, NGOs only care about assisting the Muslim community. This is a reference to Rakhine, which is home to the majority of the Muslim Rohingya population.

The Rohingya have been denied citizenship by successive governments in Myanmar, a country with a majority of Buddhists, and are viewed as unauthorized immigrants from Bangladesh, which is nearby. The UN estimates that more than 500,000 of them remain in northern Rakhine, despite the fact that many have fled the nation due to persecution.

Even though these international organizations claim to be giving to Mocha [victims], the spokesman claimed that the Rakhine community "does not receive it.". " .

While denying the claim, aid organizations told the BBC that the ethnicity of the Rohingya could have affected the choice.

"We have no doubt that the Myanmar military erects substantial obstacles. According to Claire Gibbons of the non-profit organization Partners Relief and Development, which operates in Myanmar, "[on our efforts] to assist the Rohingya and have actively reduced the human rights of the communities.".

Rohingyas in Rakhine claim that life has been very difficult since the cyclone. The ethnic Rakhine group, which has a Buddhist majority, and the Rohingya have also been at odds for many years. .

All of our homes were destroyed, Khadija, who wished to remain anonymous, said. "Some people are living in tents by the sea, and others are in their damaged homes. She resides in Dapaing, a coastal community.

Since the cyclone, numerous locals—including pregnant women—have passed away while traveling to the hospital because it frequently took a long time to find transportation, she added.

The junta has previously cut off aid, so this is not unprecedented. After Cyclone Nargis in 2008, which resulted in the deaths of over 100,000 people, they did the same.

Another reason the army might have acted in the same way this time, according to Ms. Gibbons, is that it preferred to regulate the flow of humanitarian aid to the heavily sanctioned nation.

In the same way that they did after Cyclone Nargis, they also hope to gain from aid support. According to her, some of the aid that various nations provided was sold on the market, allowing the recipients to profit. .

Following the most recent ban, there have been calls for global NGOs to lessen what some have referred to as their "overreliance" on the junta, which they claim has stifled the global response to the cyclone.

Local aid workers advise international organizations to collaborate more closely with locals who have more on the ground; some even suggest armed resistance organizations as potential partners. For instance, the Arakan Army has created its own humanitarian wing in response to the cyclone.

While waiting for assistance, Khadija and the other cyclone survivors continue to struggle.

In this extremely trying time, she says, "We don't know what will happen to us.". "We're unsure whether we'll continue to experience hunger or pass away.

. "