The Northern Ireland Protocol's European Court of Justice oversight role has been criticized by the UK government, which claims that if it remains in place, the agreement won't last.

On the other hand, the EU has asserted that the protocol's continuation without the court's supervision would be very challenging. So what exactly is the ECJ, what function does it serve in the protocol, and what alternatives are there?

The highest court in the EU, or Court of Justice of the European Union, as it is officially known. Its headquarters are in Luxembourg.

The General Court and the Court of Justice are two separate courts that make up this court system. A third court, the Civil Service Tribunal, existed from 2004 to 2016, but the General Court now handles that court's business.

In order to avoid confusion, the entire institution's activities will be discussed in this article as the European Court of Justice (ECJ).

You can use this page to find out more information or to look up a specific case.

It should not be confused with the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), which is a distinct organization and not a member of the EU.

It resolves conflicts between EU institutions and determines whether they are conducting themselves legally.

It checks that the EU's member states are adhering to their legal obligations as stated in the EU treaties and gives them the opportunity to contest EU regulations.

Upon request from national courts, it explains EU law.

All things considered, this implies that the ECJ interprets and upholds the single market's rules as well as pretty much everything else the EU does.

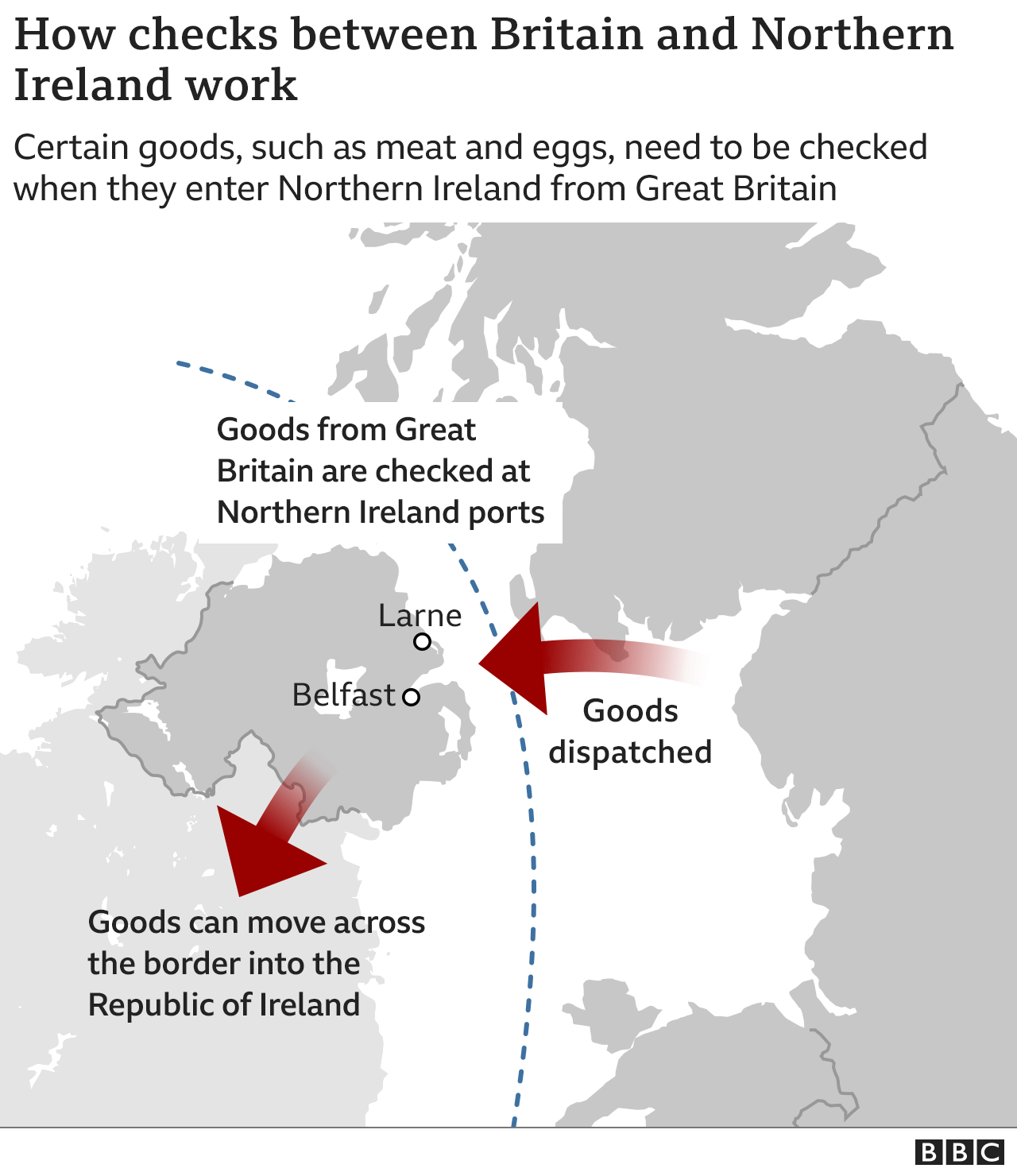

According to the protocol's rules, which were jointly decided by the UK and the EU as part of the Brexit agreement, Northern Ireland continues to adhere to EU regulations on product standards, allowing for the free movement of goods within the EU's single market.

When goods arrive at Northern Ireland's ports, they must undergo a variety of inspections and have the appropriate paperwork filled out.

According to the agreement that established the protocol, EU representatives are authorized to supervise its adoption and use.

It also declares that the ECJ has the authority to make decisions regarding EU law in Northern Ireland.

The EU could take the UK before the ECJ in the event that there was a dispute regarding compliance with applicable EU law, and the ECJ would decide whether the UK was in violation of its obligations under the protocol's terms.

The UK would take part in hearings in any cases brought before the ECJ just like an EU member state would.

Lord Frost, a former minister responsible for Brexit, wished to have the ECJ's oversight of the protocol eliminated.

In a paper released in July 2021, the government claimed that the "very specific circumstances" of the protocol negotiation were the only reason it had consented to the ECJ's involvement.

It called for a new form of government in which disagreements would be "managed collectively and ultimately through international arbitration.".

The Brexit vote can be traced back to this criticism of the ECJ's function. In fact, it is directly related to one of the issues that British Euroskeptics have long had with the EU: the fact that UK courts could be subjected to decisions made by European courts regarding EU law.

"Take back control" was a crucial part of the leave campaign's campaign during the Brexit debate.

Then at the Conservative Party conference in October 2016, the then Prime Minister Theresa May said: "We are not leaving (the EU) only to return to the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice. It won't happen like that. ".

Vague pledges to regain control over our laws overnight transformed into a very specific pledge to end the UK's participation in the ECJ. The government declared it to be unlawful.

That did not, however, prevent the government from ratifying the NI Protocol under the watchful eye of the ECJ. Lord Frost wanted to change that, specifically.

In a statement made in October 2021, Vice-President of the European Commission Maros efovi said: "I find it difficult to see how Northern Ireland would remain or would maintain access to the single market without oversight of the European Court of Justice. ".

After Lord Frost reiterated his desire to have the ECJ removed from its oversight role, Simon Coveney, the country's then-foreign minister, responded forcefully as well.

The UK's protocol demands, according to Mr. Coveney, could "cause a breakdown in relations" with the EU.

Given the extensive compromise proposals the EU is putting forth, he continued, the UK's dismissals were now "more serious.".

According to Mr. Coveney, "every time the EU puts forward new suggestions or ideas to try to solve issues, they are rejected before they are made public. This is happening again this week.".

According to him, the UK's dismissals are perceived by the EU as following "the same pattern, over and over again.".

The model of dispute resolution found in the main withdrawal agreement between the EU and Ukraine, as well as the bilateral agreements the EU has made with other neighbors, is one substitute that has been put forth.

The ECJ only hears cases involving interpreting EU law under these treaties; all other cases are heard by an arbitration panel.

One issue with this from the perspective of the EU, according to David Phinnemore, professor of European politics at Queen's University Belfast, is that the EU is clear that the ECJ, not an intermediary like the arbitration panel, is the only body that has the authority to interpret EU law.

It might, however, offer a "landing zone" for the UK government and the EU, according to Anton Spisak, trade policy lead at the Tony Blair Institute.

While the ECJ is the only body with the authority to interpret EU law, the arbitral panel serves as the "default arbitrator," according to him.

Ultimately, in his opinion, the UK is ready to accept a "more narrow role for the ECJ, but only in those circumstances where EU rules apply.".

The arbitration panel is the one who ultimately decides, but the panel must take the opinions of the ECJ into consideration, he said.

"This is how the EU has handled other third countries applying EU law in the past, and the reason why I believe it is a realistic proposal is because the EU recently put it on the table with Switzerland. ".

An additional option is something akin to the EFTA Court, which is in charge of the three nations that make up the European Economic Area (EEA): Iceland, Liechtenstein, and Norway.

Theoretically, that is an option, but it would require creating a court specifically for Northern Ireland, according to Prof. Phinnemore. ".

Moreover, he emphasized that the EFTA Court follows the ECJ's precedents in making its decisions.

The EFTA Court was not, in Mr. Spisak's opinion, a workable solution.

There is no precedent, according to Prof. Phinnemore, that permits anyone other than the ECJ to decide on EU market regulations.

"I don't see the EU straying from that; if you want to participate in the goods single market, you have to abide by EU rules.".

In a delicate discussion like this one, Mr. Spisak stated that it is helpful to begin with the fundamentals. It is simply inevitable that the ECJ will serve as the arbiter of any EU rules present in the protocol, whether they exist now or as part of a future agreement.

The ECJ must be accommodated by both parties within the protocol because it is unlikely that EU laws will not be mentioned at all. ".

However, he thought a compromise could be reached.

There is a technical fix, he said, that appears to be a more conventional international treaty but involves the ECJ in certain circumstances. Politics is the real challenge.

"The EU caving on the ECJ would send the UK the message that it is willing to renegotiate a significant portion of the protocol, which it has stated it would not do.

. "