In discussions about how to reduce violence in America, the same suggestions are frequently made, whether it be more police or more gun control. Chicago, however, is fully committing to a different tactic. Does it work?

Tim Smith realized that trouble was coming. The west side of Chicago neighborhood where he lived was rumored to be the scene of a beef between two rival gang members.

It was his responsibility to defuse the tense situation, and he recognized an opening in the form of a nearby community event that would feature food, entertainment, and a jumping pillow.

He explains, "I met them earlier that day, and I told them they could come to talk, and I also said everyone has to come 'palms up,'" meaning unarmed and non-violent.

Tim claims that when the rivals met to talk on that neutral ground, they discovered that they shared a family quickly. Their territories were divided by one of the city's main roads. A few hours earlier, the acute anger that seemed significant had begun to fade.

It's impossible to know for sure, but Tim, a street outreach worker in one of America's most violent neighborhoods, claims the encounter stopped a shooting that might have resulted in further bloodshed.

After that, he claims, "it was easy.". "Peopl were dining collectively. There was respect, but it wasn't like they were pals and hanging out. " .

Community violence intervention (CVI), a trend in crime prevention, places these kinds of on-the-ground interactions at the forefront.

At its core, CVI transforms community members who are familiar with the streets into crime-prevention specialists in the hopes that they will be able to do what police have attempted and largely failed to accomplish for years in Chicago's most violent neighborhoods: end the cycle of violence.

Despite only having a third of New York City's population, Chicago has more homicides per year than the Big Apple. Over the past few decades, violent crime has increased in Chicago even as it decreased in other significant US cities.

2014 saw a worsening of circumstances after police killed Laquan McDonald, a 17-year-old. For more than a year, city officials prevented the release of video from the shooting, deepening tensions between the public and the police. Both crime and arrests decreased.

Following George Floyd's murder, the Covid pandemic and unrest began. The following year, in 2021, Chicago experienced a high of almost 800 murders, a rate not seen in nearly 30 years.

Particular areas have a lot of concentrated violence. According to the University of Chicago's Crime Lab, only a small number of neighborhoods—mostly on the west and south sides of the city—are home to more than two-thirds of the city's murders.

By 2020, Austin and Garfield Park, two impoverished, primarily African-American neighborhoods on the west side of the city, had a murder rate of more than one per 1,000 residents, ranking them among the most dangerous urban areas in the nation.

People who are trying to stop the violence speak not only of specific high-crime neighborhoods but also of hotspots that are even more concentrated and only span a few dozen blocks.

In 2015, Teny Gross established the CVI program Institute for Nonviolence Chicago. In Austin, it's housed in a former school. The surrounding streets are .ted with boarded-up businesses and crumbling houses, the results of decades of underinvestment, and lockers and chalkboards still line the walls.

According to Mr. Gross, police officers cannot be expected to handle the vast amount of violent crime on their own. Especially when used in conjunction with initiatives that provide job training, psychological support, and other services, he claims that civil organizations can help resolve issues before they explode into murder.

Without CVI, he asserts, "you cannot transform an American city.".

There are numerous groups operating in the city right now, and they are coordinating their efforts more and more. .

Sessions at the Metropolitan Peace Academy, a citywide training facility for CVI workers, earlier this year included role-playing exercises, lessons on trauma, work skills, community organizing, and more, highlighting the wide range of activities that fall under the CVI umbrella.

The most dramatic aspect of outreach workers' jobs, however, is when they are asked to participate when tensions are at their highest – immediately following a killing. A system that sends alerts about shootings in the city was displayed by one of the workers.

This, he says, is our "call to action.".

The details are often vague, such as when a hospital sends a message with the age, sex, and time of admission of a gunshot victim. A name or even any context is frequently missing.

Then, workers look through their contacts to see if anyone is plotting revenge and speak to gang members eager to exact their revenge.

Information is not given to the police by them. Any indication that they are collaborating with law enforcement would not only make people hesitant to open up, but could also put everyone involved in danger.

Many outreach workers say it can be extremely stressful to try to prevent murders in real time, but they have done it before. The vast majority of employees have either committed violent crimes, been shot, or both.

Tim Smith, an outreach worker on the west side, was sentenced to 13 years in prison for his role in a gang fight that resulted in the death of a man.

Older prisoners, he says, taught him about black history and pushed him to consider options other than crime and prison.

He has since discovered a position where his past is an asset rather than a liability. He is a good communicator and understands how to relate to the neighborhood "shorties," young men who are involved in gangs and violent crime.

He says during a break in the training, "You have to meet people where they are. "I've been there, so I know how to talk to them. ".

Supporters of CVI point to evidence that it is effective, though it is unclear where and when it can truly make a difference given the variety of settings and tactics.

According to research from Northwestern University, over a recent five-year period, one CVI program prevented close to 400 shootings. The study contrasted neighborhoods with and without comparable CVI projects to areas where one project was active.

The study's principal investigator, Andrew Papachristos, says there are still many important issues that remain unresolved, such as how the overall ebb and flow of crime rates affects how often people are murdered. Even though there seems to be a decrease in murders in some neighborhoods, carjackings, muggings, and crime on the city's public transportation system remain stubbornly high.

He claims that while these programs frequently succeed, they occasionally fail. "But we still don't know what makes them work and what makes them not work. ".

But CVI has one significant public policy advantage in addition to the lower crime rates: it avoids the contentious discussions about policing and gun control in America, which might make it more politically acceptable.

It has received support from US President Joe Biden. Along with the billions in Covid relief funds available for such initiatives, the US Justice Department last year made a $100 million promise to CVI groups.

Large donations have also been made by private foundations and regional authorities.

But recent acts of violence have illustrated how challenging progress can be.

So far this year, there have been fewer murders overall. Chicago Police recently released a statement in which they specifically praised the work of employees who "spent time connecting with the city's young people".

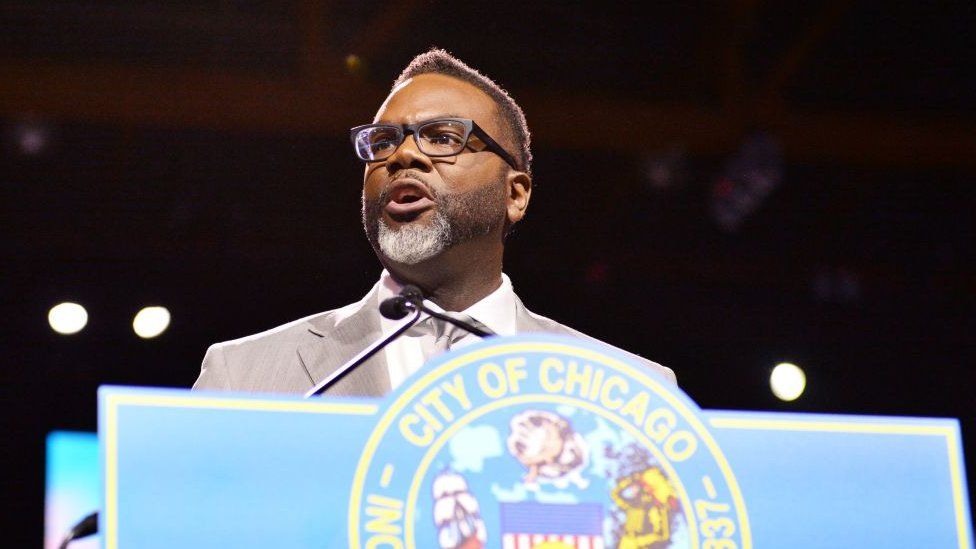

However, when the city's new mayor, Brandon Johnson, pledged $2.15 million in funding and 30 peacekeepers over the recent Memorial Day weekend, that attempt was unsuccessful. One of the bloodiest Memorial Day weekends in the city in a long time, there were over 50 shootings and 11 fatalities.

That raises a significant issue: Will public officials and for-profit organizations continue to support community initiatives even if crime rates rise once more, or will CVI follow a long list of other crime-prevention trends?

Experts and outreach personnel currently have another rarity in recent years: a glimmer of hope. According to Tim Smith, he is attempting to uphold the tenuous peace in his neighborhood.

Before going out and using violence, he says, "Youth feel a lot more comfortable coming to us.". "We're spreading the word and letting people know there's a place they can feel safe and someone they can just talk to. ".

The truce he negotiated earlier this year, he claims, is just the tip of his work because he is aware of the enormous challenges that lie ahead.

One of his participants landing a job, he says, is what comes to mind when he thinks of a real success story. "Getting people to put down their firearms? That's just another day, where hopefully I avert a shooting or a jail sentence," the man said.

. "