Late in November 2018, Ethiopian university student Moti Dereje logged into his Facebook account expecting to see the typical updates from his friends and family.

The 19-year-old, who was enrolled in a university in Addis Abeba's capital, saw a shocking post instead.

He said on the BBC podcast The Comb, "I saw my father's dead body lying there as I refreshed my news feed.".

In addition to being horrified by the graphic image, Mr. Moti was also shocked to learn that his father had been murdered.

"At that point, I kind of froze. I found it to be really shocking," he claims.

Social media has been inundated with graphic images and videos, misinformation, and posts encouraging violence as a result of the political unrest Ethiopia has experienced in various regions over the past few years.

A greater effort to moderate the platforms and remove such content before it causes harm has been urged by activists.

For Mr. Moti, the image wasn't removed; instead, he started to see more posts with the same image.

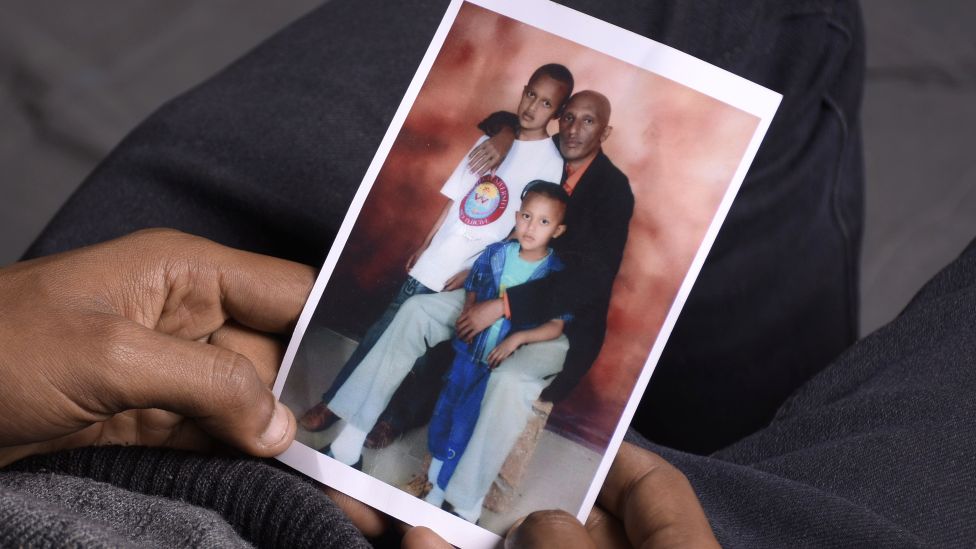

During a political assassination in western Oromia, his father, a former member of parliament who was now a university administrator, was the victim.

At the time, there were many assassinations in the area as it went through a time of unrest.

It appears as though they were celebrating killing him. It was actually painful," says Mr. Moti.

The BBC has seen 15 of these posts, which, according to Mr. Moti, he reported to Facebook in the hopes that they would be removed.

Facebook's Community Standards state that upon a family member's request, it will take down "videos and photos that show the violent death of someone.".

But despite Mr. Moti's repeated reports that he made about the posts, they persisted online for more than four years.

Some of the images only had a graphic content warning.

"When I'm feeling down, I can't help but keep looking up his name and reading the posts with my hand in my pocket. I think I've been traumatized," Mr. Moti claims.

When the BBC contacted Facebook's parent company Meta for comment, it was agreed that although the images on their own did not violate the company's policy on violent and graphic content, it would remove the posts at the request of a family member.

All posts displaying the photograph of Mr. Moti's deceased father have since been deleted.

Although Meta informed the BBC that it was testing a new form to support this, there is currently no way for family members to submit these requests through Facebook's reporting system.

The amount of offensive language and graphic material shared on Ethiopian social media has been raising concerns.

Prior to 2020, this was an issue, but after the war in the northern Tigray region broke out in November of that year, the amount of violence that was appearing in people's newsfeeds skyrocketed.

The Facebook Oversight Board recommended in 2021 that the company commission an unbiased investigation into Ethiopia in particular to examine how the platform has been used to spread hate speech and escalate the violence.

This analysis has not been conducted. A spokesperson for Meta responded to a question from the BBC about this by citing a previous response in which the company had stated that it would evaluate the viability of such a review and that it had previously carried out various types of human rights due diligence in relation to Ethiopia.

Two Ethiopians who claim Facebook's algorithm aided in the viral spread of hate and violence announced last year that they were suing Meta.

Meta responded that it had made significant investments in technology and moderation to eliminate hate.

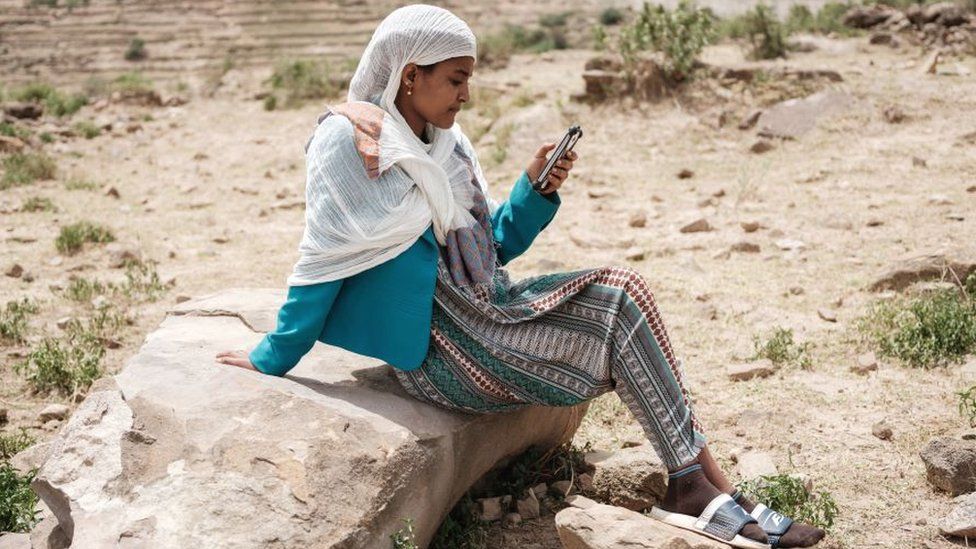

Rehobot Ayalew, a fact-checking expert based in Addis Abeba, queries the extent to which social media companies are addressing the issue.

She told The Comb, "I don't think the platforms are giving Ethiopia that much attention.

"I know Facebook claims to have moderators who concentrate on Ethiopia and speak Amharic and Tigrinya, but we don't know how many. They are actually working from Kenya rather than Ethiopia.

As a result, violent content frequently remains online for far too long, according to Ms. Rehobot.

A toxic post typically takes a while to be removed, according to her.

Ms. Rehobot makes reference to a video of a Tigrayan man being burned alive that was widely circulated in March 2022.

First off, she says, "artificial intelligence by itself should have removed it.".

"After it was reported, it should have been taken down immediately, but it stayed for a while.

A Meta representative told the BBC that the company has strict guidelines outlining what is and isn't permitted on Facebook and Instagram. These rules forbid the expression of hatred or the incitement of violence, and we make significant investments in personnel and equipment to find and eliminate such content.

The most widely used languages in the nation, including Amharic, Oromo, Somali, and Tigrinya, are among those in which we employ personnel with local knowledge and expertise. We also continuously improve our capacity to identify unlawful content in these languages.

Public awareness of heinous human rights violations can be useful, but such information can also be used to incite rage and place blame on particular ethnic groups or people.

Thousands, if not millions, of Ethiopians continue to experience the traumatic effects of viewing such content.

A peace agreement was signed in November of last year with the intention of ending the Tigrayan civil war and beginning to address the terrible humanitarian crisis it had sparked.

The estimated death toll is in the hundreds of thousands, with the majority of those passing away from hunger and a lack of medical supplies brought on by the fighting.

Oromia, which has experienced a growing uprising, is still roiled in unrest at this time.

Activists worry that the violence that permeates social media will make it difficult for these individuals to reconcile.

According to Ms. Rehobot, "People have a tendency to believe [the posts] and act upon them, so widespread violent and destructive images can undoubtedly slow the process of peace and reconciliation.

At the age of 23, Mr. Moti is making an effort to move past his past by pursuing a career as a videographer and photographer and even creating a documentary about his own experience.

In an effort to fight back, he says, "I think it's time for me to tell my own story. If I succeed, maybe I can bring about a change.".

However, he asserts that until it is curbed, the prevalence of graphic content will trouble him.

Because of the war in Ethiopia, I am deeply saddened whenever a dead body is posted online or on Facebook. There will be someone who experiences what I have.

It really makes me sick.

Play the complete episode of The Comb podcast. when violent behavior spreads like wildfire.