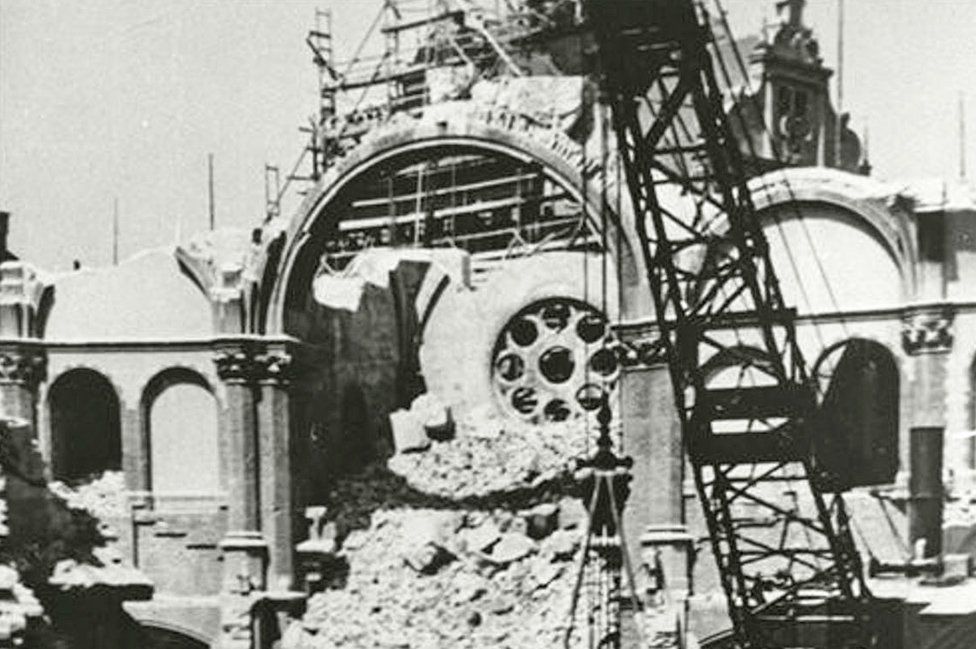

Construction workers discovered building debris from Munich's main synagogue in a nearby river, 85 years after Adolf Hitler ordered its destruction.

They discovered synagogue columns as well as a stone tablet with some of the Ten Commandments written on it.

The discovery has delighted members of the local Jewish community and others.

Bernhard Purin, director of the Jewish museum in Munich, said, "We never thought we would find anything from it.

Since the building was demolished in June 1938 as a result of Hitler's demand that it be removed as an "eyesore," there has been no trace of it. Five months later, in the deadly pogrom known as Kristallnacht, Jews, synagogues, and Jewish-owned businesses were attacked throughout Nazi Germany.

After working in Jewish museums for 30 years, Mr. Purin told the BBC, "Yesterday I saw [the remains] for the first time, and it was one of the most moving moments, especially seeing the plaque of the Ten Commandments not seen since 1938.".

Since the historic structure was used to construct a weir 11 years after World War Two, it is believed that debris from it has been deposited in the River Isar.

One of the most well-known pre-war landmarks in Munich, the synagogue, housed the stone tablet that was originally found above the Ark (which held the Torah) on the eastern wall. A Karstadt department store has since taken over the former location.

A little less than a quarter of the tablet was missing, according to Mr. Purin, and this was the biggest finding so far.

The debris from the synagogue's destruction was reportedly kept on the site west of Munich by the Leonhard Moll building company until 1956.

The large Grosshesseloher weir was then renovated using approximately 150 tonnes of debris, mostly from the synagogue but also from buildings bombed during the war.

Charlotte Knobloch, the 90-year-old leader of the Jewish community in Munich, was overjoyed by the discovery because she had attended services in the old synagogue as a young girl before it was destroyed.

She informed the Münchner Merkur newspaper that "these stones are a part of Munich's Jewish history.". "I honestly didn't think fragments would survive, much less that we'd see them. ".

The discovery of the remnants of such a magnificent building, according to Munich Mayor Dieter Reiter, was a "stroke of luck," he told public broadcaster BR. According to his deputy Katrin Habenschaden, the city had a historical obligation to secure the find and give it back to the Jewish community.