There is a buzz in Esther Abu's home because her mother and daughters have just learned about a new law that will give loans to underprivileged Nigerian families so they can send their kids to college.

Next month, the teenage daughter of Mrs. Abu who speaks like she is rapping will graduate from secondary school. She adores computer engineering but is aware that her mother, a single parent whose street sweeper salary barely provides enough food for the family - and must be supplemented by alms given primarily by her church - does not have enough money to send her to university.

Her eldest graduated from secondary school two years ago, and she immediately started working as a hair stylist to help support the family, who reside in the crowded Abuja suburb of Mararaba.

The dream I had as a young girl was to become a doctor, says Eunice, now 21.

Now that the government has announced it will start paying people from such low socioeconomic backgrounds for their tuition, both have a chance—however slim—of reviving their dreams. However, there are a lot of issues with the plan.

President Bola Tinubu has enacted a number of reforms quickly since taking office at the end of May, including ending fuel subsidies, devaluing the naira, removing the head of the central bank and security chiefs, and his most recent initiative is to revive Nigeria's failing tertiary education system.

The government has kept tuition costs low for many years in an effort to promote enrollment in a nation where many people live in poverty and there is a high rate of illiteracy.

Comparatively, medical students at the University of Ghana in Accra pay 3,500 cedis (£242, $308) per year, compared to just 25,000 naira (£32; $26) at the University of Lagos in Nigeria's richest state.

Over time, however, such low fees have not been matched by government funding, resulting in schools with out-of-date technology, crammed classrooms, and low salaries for lecturers and other staff.

In Nigeria, the average university professor makes less than 500,000 naira (£570; $725) per month, compared to 160,000 for graduate assistants.

Due to persistent strikes brought on by these circumstances, universities were shut down for eight months in 2017 – the ninth such interruption in the previous 13 years.

People no longer have confidence in Nigeria's public universities due to strikes and inadequate funding, which has led them to enroll in pricey private institutions or to study abroad, particularly in Eastern Europe.

President Tinubu has given universities free rein to raise tuition fees, which the government believes students from low-income families can now afford because of the loans.

The program "will increase access to education for all Nigerians regardless of their backgrounds," according to the president.

Two years after the recipients have finished the post-graduate paramilitary service that is a requirement for the loan, they will begin making monthly deductions from their salaries equal to 10% of their salaries.

Mrs. Abu muffled the room with her question, "But what if they finish school and don't get a job?".

Since the program's announcement two weeks ago, students and their parents have been asking this question all over Nigeria.

Numerous graduates flood the Nigerian labor market each year, but few of them are successful in finding employment.

In the most recent survey, which was conducted in 2020, one in three people who wanted to work were unemployed, and millions of graduates were working in jobs that were beneath their level of education, like being hair stylists.

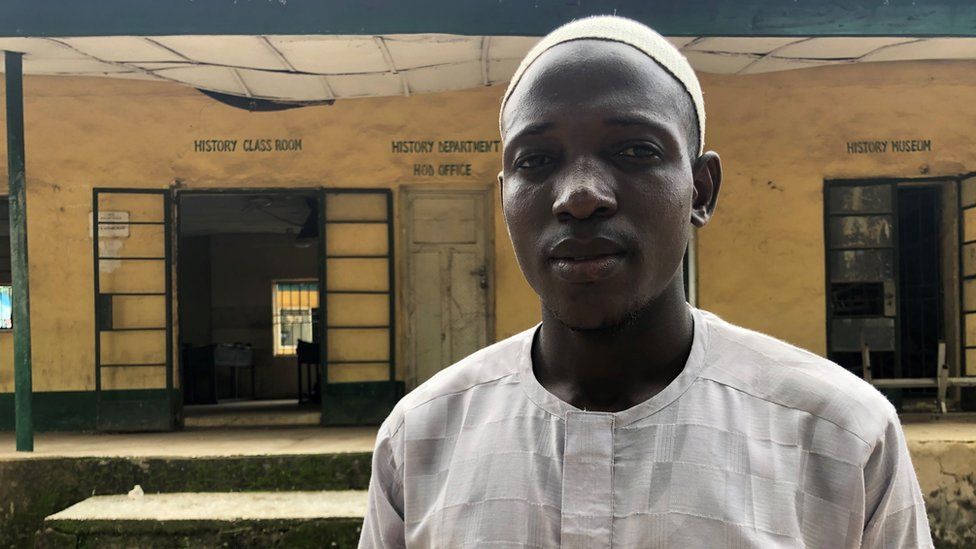

According to Ayuba Mayah, a student at the College of Education in Zuba, Abuja, "I know at least 200 graduates in my village who returned to farming after going to school because there were no jobs.".

In order to avoid carrying that weight around his neck while looking for a job after graduating, he says he is not going to take the loan. He is working to pay for his education instead.

Aminu Sadiya and Mercy Sunday, who are both economics majors at the same university, concur that finding work is what worries them most about taking out the loan.

Ms. Sunday, whose parents are farmers, claims, "My parents did not think of a loan before they sent me to school, they will find a way to pay the fees.".

Although Mr. Tinubu has pledged to create millions of jobs for young people in order to cut the unemployment rate in half in three years, the new law says nothing about graduates who are unable to repay their loans because they are out of work.

However, those who go into business for themselves run the risk of receiving a two-year prison sentence or fine if they refuse to repay the loan with 10% of their monthly earnings.

But the loan is not available to everyone; it is only given to students from families with an annual income of less than 500,000 naira.

Millions could theoretically gain, but obtaining a loan has strict requirements.

Poor families will need to provide bank statements, which many of them are unlikely to have, in order to demonstrate their meager income.

A minimum of two guarantors must be provided by applicants.

- a senior government employee.

- at least ten years of experience as a lawyer.

- Justice of the peace or judicial official.

Poor Nigerians are unlikely to know such people, and even if they do, their chances of having that person sign on as a loan guarantor are slim.

Despite fulfilling the requirements, applicants are not guaranteed to receive a loan because it depends on available funds.

According to Vanessa Macaulay, a third-year mass communication student at the Yaba College of Technology in Lagos, "They should just say they don't want anyone to access the loan.".

The loan conditions are also deemed "not practicable" by the president of the lecturers' union at universities, who also notes that more than 90% of students won't be able to fulfill the "requirements".

However, other academics claim that despite tuition fees of just 30,000 naira (£34, $43) per semester, many of their students are unable to pay. One such academic is Professor Mudashiru Mohammed, who oversees the Education Management department at the state-owned Lagos State University.

In a nation where most people view government loans as free money, he claims that the requirements were necessary to ensure that people paid up.

Although it can be difficult to gauge the financial status of students in public tertiary institutions, many University of Abuja students have told the BBC that they come from low-income families.

Parents and guardians who work as company drivers, private security officers, and junior civil servants pay for their children's education.

Even though these families are not wealthy by Nigerian standards, their combined earnings are frequently just above the cutoff, making the loan unaffordable.

These families have already been negatively impacted by the recent increases in food prices as well as the doubled cost of transportation.

They now have to deal with tuition fees that have increased by as much as 200 percent at some universities, which have been considering increases since last year.

The loan is only for tuition; it does not cover other expenses like housing and food, which typically make up a larger portion of the overall cost of attending university.

Mrs. Abu, whose home has been quiet for some time, asks, "If they are not paying for everything, then what is the point of it? Who will buy books, pay for hostel, and provide food?".

Caleb Issac, a part-time student at the National Open University in Abuja who is self-sponsored, says "They should have made the loans available to every student.".

He worries that a fee increase will be difficult on him because he works as a marketer for a transportation company in his spare time.

This is not Nigeria's first attempt at a student loan; the military government's first attempt in 1972 failed because recipients refused to pay back, according to Prof. Mohammed.

Mrs. Abu suggests that the president should have prioritized job creation first.

The lack of employment, additional costs, and a lack of clarity regarding what will happen to workers who miss payments make the loan unworkable for her family, she claims.

She says it would be better for her daughters to learn a trade and work odd jobs rather than enroll in school and risk going to jail.