Abdul beats the heads of the poppies as hard as he can while holding an AK-47 assault rifle slung over his left shoulder and a large stick in his right hand. The stalks and sap from the poppy bulb fly through the air, emitting the distinct, acrid scent of opium in its most unprocessed state. .

The poppy crop that covered the small field is quickly destroyed by Abdul and a dozen other men. The armed men then board a pickup truck and proceed to the next farm while donning shalwar kameez, a traditional Afghan tunic with loose-fitting trousers. The majority of the men have long beards, and some have eyes that have been lined with kohl.

We were granted rare permission to accompany the men on one of their patrols to stop the cultivation of poppies. The men are members of a Taliban anti-narcotics unit in the eastern Afghan province of Nangarhar. The men were involved in a conflict to seize control of the nation less than two years ago as insurgent fighters. They are now ruling and carrying out their leader's commands after winning the battle.

The cultivation of the poppy, from which opium, the primary component of the drug heroin, can be extracted, was sternly forbade by Taliban supreme leader Haibatullah Akhundzada in April 2022. Anyone who disobeyed the prohibition would have their field destroyed and face Sharia-compliant punishment.

A Taliban spokesman told the BBC that they enacted the ban because it violates their religious principles and is harmful because opium, which is made from poppy seed capsules, is used in it. More than 80% of the opium consumed worldwide used to be produced in Afghanistan. 95 percent of the heroin sold in Europe is made from opium from Afghanistan.

The BBC has now traveled to Afghanistan to investigate the effects of the direct action on the cultivation of opium poppies using satellite analysis. The Taliban's top brass seems to have done a better job than anyone else of eradicating cultivation.

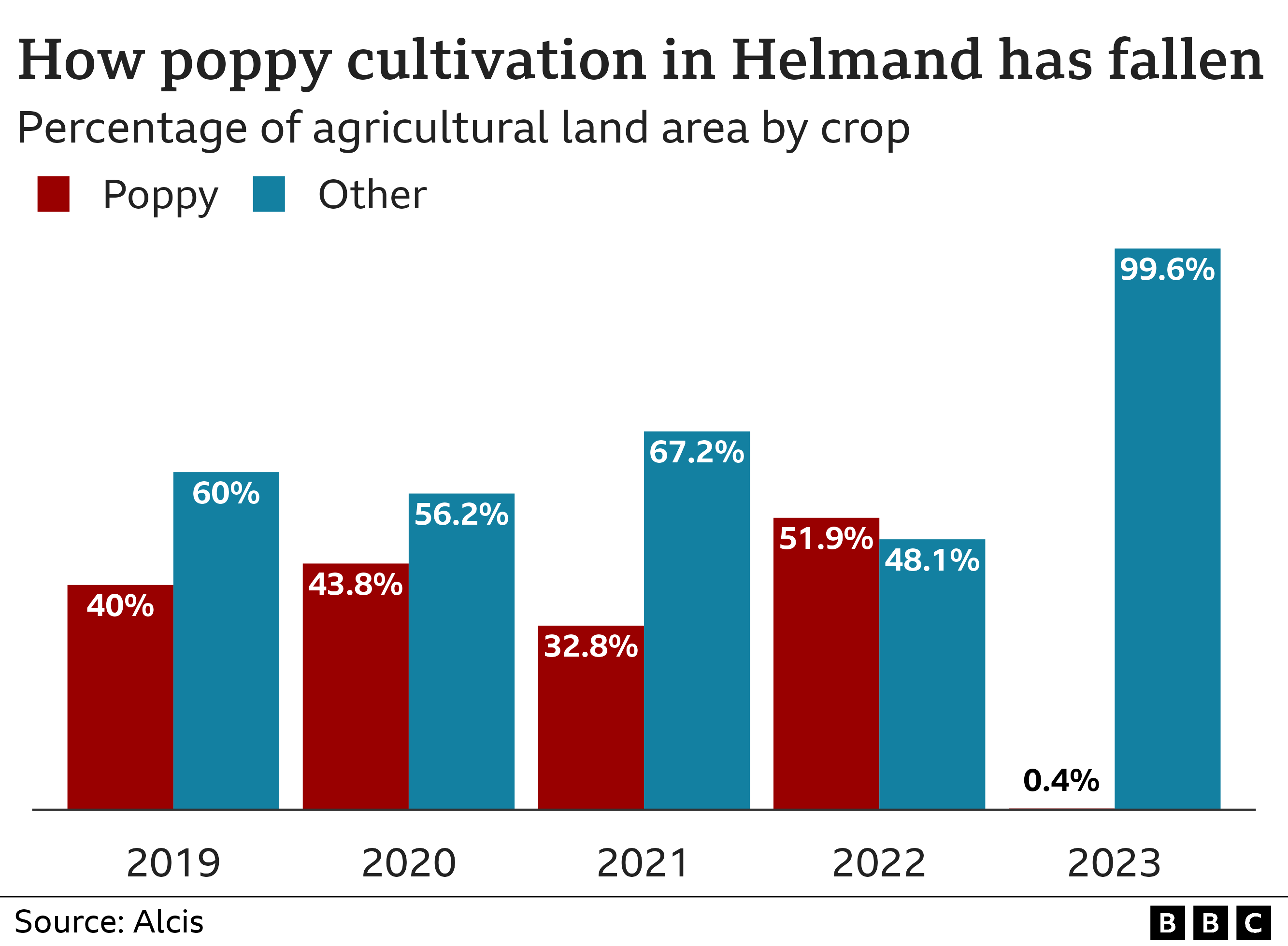

In the main opium-producing provinces, we discovered a sharp decline in poppy growth. According to one expert, annual cultivation may be by as much as 80% from the previous year. Poppies have been replaced by less lucrative wheat crops, and many farmers claim that their financial situation has suffered as a result.

To see the situation firsthand, we traveled to the provinces of Nangarhar, Kandahar, and Helmand; we rode on muddy, winding roads; we hiked for hours through farmland; and we jumped across gurgling streams.

The 2022 opium harvest, which increased by a third over 2021, according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), was exempt from the Taliban decree.

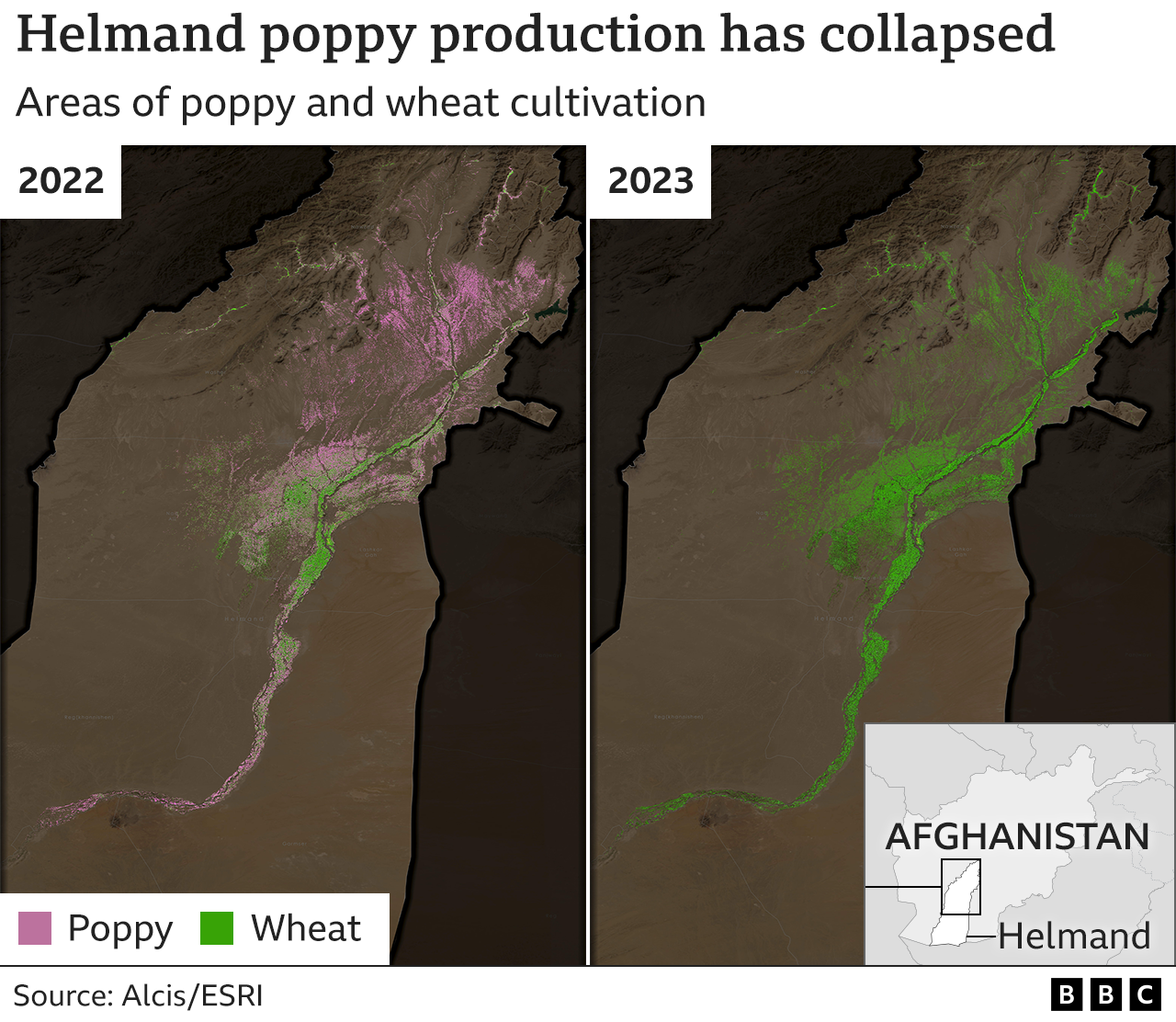

However, this year is very different. Imagery captured from above supports the evidence we saw on the ground.

Working with the UK company Alcis, a satellite analysis specialist, is David Mansfield, a recognized authority on the drug trade in Afghanistan.

The likelihood of cultivation is that it will be less than 20% of what it was in 2022. He claims that the magnitude of the reduction will be unprecedented.

The crops of farmers who haven't followed the ban have been destroyed by Taliban fighters because a lot of them have.

The commander of the Taliban patrol unit we are with in Nangarhar, Toor Khan, informs us that his men have been razing poppy fields for almost five months and have cleared tens of thousands of hectares of the crop.

One woman yells angrily at the Taliban unit as they burn her poppy field, "You're destroying my field, God destroy your home.".

"This morning, I had advised you to destroy it on your own. Toor Khan screams back, "You didn't, so now I have to. She goes inside to hide.

The Taliban kidnap her son; a few hours later, they release him after giving him a warning.

Because there have been instances of resistance from enraged locals in this area, the Taliban arrive armed and in large numbers. During the eradication campaign, shootings claimed the lives of at least one civilian, and there have also reportedly been other violent clashes.

Farmer Ali Mohammad Mia has a stricken look on his face as he watches the unit destroy his field. Once finished, the ground is covered in pink poppies, green bulbs, and broken stems.

Why did he cultivate poppy despite the ban, we ask.

"If you have no food at home, and your children are going hungry, what else would you do," he says. "We don't have large pieces of land. If we grew wheat on them we would make a fraction of what we could from opium. ".

What is remarkable is the speed at which the Taliban carry out the job using only sticks. Six fields, each between 200-300 sq m in size, are cleared in just over half an hour.

How do they feel about destroying a source of income for their own people who are going hungry, we ask Toor Khan.

"It is the order of our leader. Our allegiance to him is such that if he told my friend to hang me, I would accept it and surrender myself to my friend," he says.

Helmand province in the south-west used to be Afghanistan's opium heartland, producing more than half of the country's opium. We travel there independently of the Taliban's anti-narcotics unit, to see first-hand how it now looks.

Last year when we were in the province, we saw swathes of land covered with poppy fields. This time we can't spot a single field of the crop.

Alcis's analysis shows that poppy cultivation in Helmand has reduced by more than 99 percent. "The high resolution imagery of Helmand province shows that poppy cultivation is down to less than 1,000 hectares when it was 129,000 hectares the previous year," says David Mansfield.

We meet farmer Niamatullah Dilsoz in the Marjah district - south of Helmand's capital, Lashkar Gah - while he is harvesting wheat. Last year, he grew poppy in the same field. He tells us farmers in Helmand, a Taliban stronghold, have all but complied with the ban.

"A few farmers tried to grow poppy in their courtyards hidden behind walls, but the Taliban found out and destroyed those fields," Niamatullah says.

Except for the sound of wheat stalks being cut and the calls of birds, it is quiet in the farm. During the war, the field was a front line. Helmand was where UK troops had a base and where they fought some of their fiercest battles.

Niamatullah is in his early twenties. This is the first time in his life that he doesn't fear being hit by a bomb when venturing out. But for a people already battered by a long war, the opium ban has struck a crushing blow, coming as it does amid an economic collapse which has caused near universal poverty in Afghanistan. Two thirds of the population don't know where their next meal will come from.

"We are very upset. Wheat earns us less than a quarter of what we used to make from opium," he says. "I can't meet my family's needs. I've had to take a loan. Hunger is at its peak and we haven't got any help from the government. ".

We ask Zabiullah Mujahid, the Taliban government's main spokesman, what his government is doing to help people.

"We know that people are very poor and they are suffering. But opium's harm outweighed its benefits. Four million of our people from a population of 37 million were suffering from drug addiction. That is a big number," he says. "As far as alternative sources of livelihood go, we want the international community to help Afghans who are facing losses. ".

He rejects assertions by the UN, the US and other governments that opium was a major source of income for the Taliban when they were fighting against Western forces and the previous Afghan regime. .

How can they expect international organisations to help, when the Taliban government has jeopardised their operations and funding by banning women from working for all NGOs, we ask.

"The international community should not link humanitarian issues with political matters," replies Mujahid. "Opium isn't just harming Afghanistan, the whole world is affected by it. If the world is saved from this big evil then it is only fair that Afghan people receive help in return. ".

At the source, the impact of the ban on opium prices is already evident. In Kandahar, the spiritual home of the Taliban and traditionally another major poppy-growing area, we meet a farmer who is holding on to a small stash of his harvest from last year - two plastic bags, each about the size of a football, filled with dark, smelly opium resin. We're hiding his identity to protect him.

"Last year just before the ban, I sold a bag like this for a fifth of what I could get now. I'm waiting for the price to increase further so it can sustain my family for longer. Our situation is very bad. I've already taken a loan to buy food and clothes. Of course, I know opium is harmful, but what's the alternative?" he asks.

It might take a while for the price impact to filter down the chain of illicit drug trafficking to the street price of heroin.

"While opium and heroin prices remain at a 20-year high, they've been falling over the last six months, despite such low levels of poppy cultivation this year," says Mansfield. "This suggests there are significant stocks in the system, and the production and trade in heroin continues. Seizures in neighbouring states and beyond also indicate a shortage of heroin is not imminent. " .

Mike Trace - a former UNODC official - was a senior UK government drugs policy advisor when the Taliban's first regime banned opium cultivation in 2000, a year before the US-led invasion of Afghanistan.

"That didn't lead to a massive and immediate impact on Western prices and markets, because there is an awful lot of stockpiling by the actors along that drug-trafficking route," he says. "That's the nature of the market and it hasn't fundamentally changed for the last 20 years. ".

Billions of dollars were spent by the US in Afghanistan to try to eradicate opium production and trafficking, in the hope of cutting the Taliban's source of funding.

They launched airstrikes on poppy fields in Taliban-controlled territory, burnt opium stocks and conducted raids on drug laboratories.

But opium was also grown freely in areas controlled by the US-backed former Afghan regime, something the BBC witnessed prior to the Taliban takeover in 2021.

For now, the Taliban appears to have accomplished in Afghanistan what the West couldn't. But there are questions about how long they can sustain it. .

As far as heroin addiction in the UK and the rest of Europe goes, Mike Trace says a dramatic reduction in opium cultivation in Afghanistan is likely to alter the type of narcotics consumed. "People are likely to turn to synthetic drugs which can be far more nasty than opium. ".

Additional reporting by Imogen Anderson and Rachel Wright .