Ruchelle Barrie recalls not fitting in at school.

In Mumbai, India, where most of her classmates preferred speaking Hindi or Marathi, she stood out among her classmates because her name was frequently misspelled and mispronounced and because she spoke English so well.

But along with that spotlight came inquiries like: Where are you from? Do your relatives come from India? And what exactly is an Anglo-Indian?

The last question was the most difficult to respond to, so she learned to avoid it by hiding what was a "core aspect" of her identity from view in public.

People with British and Indian ancestry are frequently referred to as Anglo-Indians. However, according to the law, it refers to Indian citizens who are descended from Europeans on their father's side. This means that, in light of India's long history of colonization, their paternal ancestors may have been British, French, or Portuguese.

Ms. Barrie, who is now 30 years old and of British and French ancestry on her mother's side, continues to struggle with her identity and sense of belonging.

But now that I'm more at ease with it, I want to learn more about my ancestry, she claims. She has therefore joined a Facebook community for Anglo-Indians where she asks queries about the group and its culture.

Young Anglo-Indians like Ms. Barrie are attempting to uncover their ancestry and protect the cultural heritage of their community, which many fear is in danger of being lost.

Some are finding ways to preserve shared memories and heirloom recipes, while others are tracing their family's history through research and documentation and reestablishing contact with long-lost relatives. In the process, they are coming up with fresh strategies for encouraging a sense of community within the dispersed, shrinking group.

Despite the fact that there are no official statistics to support it, experts claim that the number of Anglo-Indians has steadily decreased since the British left India in 1947. Only 296 Anglo-Indians were counted in India's 2011 census; this number was deemed "ridiculous" by community members.

There are between 350,000 and 400,000 Anglo-Indians in the nation, according to Clive Van Buerle, a member of the All-India Anglo-Indian Association's governing body.

Many people immigrated to nations like England, Australia, and Canada, particularly in the years following India's independence in 1947. Since then, a lot of people have also married people from outside the community, which has diluted their culture and mixed it with others.

The Anglo-Indian community has a long history that dates back to the 16th century, when the Portuguese began to colonize parts of India. In his book The Anglo Indians: A Portrait of a Community, author Barry O'Brien claims that the Portuguese encouraged soldiers to wed native women in order to "create a community that would be loyal to the colonisers, yet at ease living in the colonies.". Later, the British followed suit and used this tactic.

According to scholar Merin Simi Raj, "the Anglo-Indian identity developed out of this fusing together of eastern and western cultures.".

However, this mingling of cultures has also caused discomfort and alienation.

Because of their mixed race and dark skin, the British historically discriminated against the community. Because of their allegiance to the crown, the native Indians also had a negative opinion of them, according to Ms. Raj.

Anglo-Indians were furious when their quota of two parliamentary seats was eliminated in 2019. This shows that the feeling of alienation hasn't entirely vanished.

Mr. Van Buerle says, "It's like your government doesn't recognize your identity.".

Individuals like Ms. Barrie are creating online communities of kinship and support while Anglo-Indian associations fight for political representation.

According to Ms. Barrie, she grew up in a "pukka Anglo-Indian home," enjoying dishes like meat ball curry, coconut rice, and devil chutney while listening to country music legends Merle Haggard and Buck Owens. Even then, she claims, she's eager to learn more about her neighborhood, from colonial dish recipes to details about long-lost relatives.

According to Bridget White-Kumar, who has written several cookbooks, many young people are searching for "easier, simpler, and stress-free ways" to prepare Anglo-Indian food. Her most recent book, for example, has "easy recipes to cook Anglo-Indian grub in a microwave oven.".

It's crucial to preserve our recipes by passing them on to younger generations, according to the Anglo-Indian community, which has contributed to and borrowed from India's culinary landscape.

Many people are doing family history research to better understand their own identities.

Muna Beatty, who lives in Bangalore, and her husband Michael use genealogy websites to find old records, such as birth, death, and marriage certificates, and travel to military facilities, places of worship, cemeteries, and old colonial homes to learn where their ancestors once resided, carried out employment, or were interred.

They have established a WhatsApp group called Finding the Beattys because, according to Ms. Beatty, the quest has allowed them to get in touch with distant relatives.

The exercise has given Marcelle Britto a better understanding of her mother's special childhood. Her mother, who descended from Irish immigrants on her father's side, lived in a vast colonial bungalow with dozens of domestic servants and was frequently invited to tea parties and ballroom dances. Her life was very different from hers.

Ms. Britto was able to find her ancestors as far back as the 1700s. The stories my mother told me and my own mixed identity now make more sense, she claims.

According to Mr. Van Buerle, Anglo-Indians wanted to know about their ancestry until a few decades ago because it might help them immigrate abroad. However, since the community has successfully assimilated in India, fewer people are leaving the country.

In his words, "the quest to understand one's ancestry and identity is no longer motivated by a need for proof, but rather a need for meaning - it's an exciting journey to know more about one's self and history.".

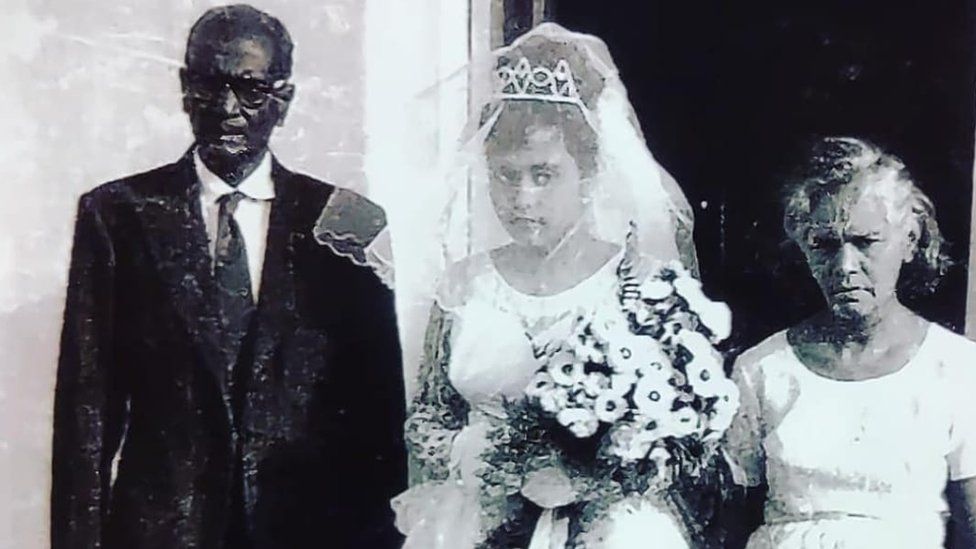

Anglo Indian Stories, a crowdsourced project on social media run by Hyderabad-based Cecilia Abraham, 47, invites users to share old memories and family photos.

Despite having a very "Anglo-Indian upbringing," Ms. Abraham claims she had little knowledge of her ancestry. Her father liked to refer to himself as "an Indian Christian.".

One of the myths about the community is that Anglo-Indians are uneducated, excessive drinkers, and partygoers, according to her. "My father didn't want people to view us that way,' she said. ".

The project's contributors have provided descriptions of their families' involvement with the Indian military and railways as well as life both before and after independence. Some people express their pain over losing touch with their close relatives.

Ms. Abraham wants her project to encourage self-confidence in people.

When we enjoy something, she explains, "we talk about it; we take care of it.". And in that way, things, including cultures, are preserved for upcoming generations.

. "