The healthcare system in India needs nurses and midwives, but there are problems because of high demand and scarce funding. Kathija Bibi, a recently retired nurse who received a government honor for supervising more than 10,000 successful deliveries, reflects on the shifts in perceptions of women's healthcare over the course of her 33-year career.

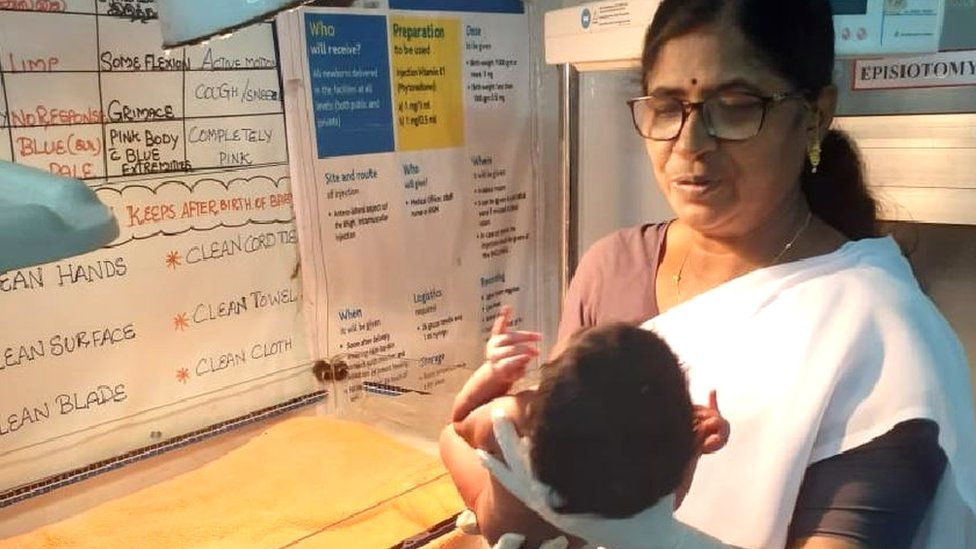

Kathija Bibi, 60, considers this to be the pinnacle of her career. "I am proud that not a single one of the 10,000 babies I delivered died on my watch," she says.

Health minister for the state, Ma. According to Subramanian, who spoke to the BBC, Khatija recently received a government honor for her years of service during which no fatalities were reported.

India has changed from a nation with a high maternal mortality rate to one that is more in line with the global average during the three decades she worked at a public health facility in the southern state of Tamil Nadu. She claims that people's attitudes toward having fewer children and the birth of girls have improved.

In 1990, when Kathija started working, she was already expecting a child.

I was assisting other women despite being seven months pregnant. I took a brief two-month maternity leave before going back to work," Kathija recalls. Making women feel at ease and confident is my top priority because I am aware of how anxious they can be during labor. " .

Having retired in June, Kathija exudes serenity. If she noticed any complications, she immediately sent pregnant women to the district hospital because her clinic, in the primarily rural town of Villupuram, 150 km (93 miles) south of Chennai city, is not equipped to perform Caesarean sections.

Zulaika, Kathija's mother, a former village nurse, serves as an example. In my younger years, I enjoyed playing with syringes. I became so accustomed to the hospital odor," she reflects.

She was aware of the value of her mother's efforts to provide healthcare to rural women who were underprivileged and illiterate from a young age. Private hospitals weren't common at the time, so women from all walks of life relied on the state maternity home, now known as a primary health center.

Two additional nurses, seven assistants, and one doctor were present when Kathija began working there. In the beginning years, work was extremely hectic. My inability to care for my kids. I skipped family gatherings. However, I learned a great deal from those times. " .

The maternal mortality rate (MMR) in India in 1990 was 556 deaths per 100,000 live births. India recorded 88 infant deaths for every 1,000 live births in that same year.

The infant mortality rate is 27 per 1,000 live births, according to the most recent government statistics, and the MMR is 97 per 100,000 live births.

Kathija credits this development to government spending on healthcare in rural areas and rising female literacy rates.

Kathija usually only deals with one or two births per day, but she can clearly recall the day when she was busiest. My life's busiest day was March 8, 2000. People welcomed her as she entered the clinic because it was International Women's Day. "I observed two laboring women standing by for me. I assisted in the birth of their children. Six more women later entered our clinic. ".

Even though Kathija only had one assistant to assist her, the pressure soon vanished. "That day, as I was about to leave, I heard babies crying. It was a pleasant experience. " .

50 sets of twins and one set of triplets, according to the nurse, were born with her assistance.

Kathija now claims that women from affluent families favor going to private hospitals. A rise in Caesarean sections has also been observed by her.

"My mother witnessed numerous deaths related to childbirth. According to Kathija, Caesareans have saved countless lives. "When I first started, women were afraid of surgery. However, many people today are choosing surgery over natural birth out of fear. ".

Over the past three decades, as rural households' incomes have increased, so have the challenges that come with it. "Previously, there were very few cases of gestational diabetes. But now, it's a very common occurrence. '' .

The number of requests Kathija now receives from husbands eager to be present during their wives' deliveries indicates a significant social shift.

"I have lived through both good and bad times. Some husbands would refuse to even see their wives if she gave birth to a girl. If she delivered a second or third girl, some women would sob hysterically. ".

The Indian government outlawed doctors telling parents a baby's gender in the 1990s because cases of sex-selective abortions and infanticide were so widely documented. To care for unwanted girls, the Tamil Nadu government also introduced the "Cradle Baby Scheme.". The situation has changed, though, Kathija notes. Regardless of gender, a lot of couples only want two kids. ".

She knows what she will miss but doesn't have any concrete plans for her life after retirement.

She says, "I always eagerly anticipate hearing the shrill and piercing first cry of a new-born.".

When they hear their babies cry, even women who have a difficult labor forget everything and begin to smile. It was incredibly thrilling for me to witness that relief. All these years, it was a soul-searching journey for me. ".

the YouTube channel for BBC News India. Go here by clicking. to subscribe and watch our explainers, features, and documentaries.