Usually when the poor French suburbs make headlines, it's because they're on fire.

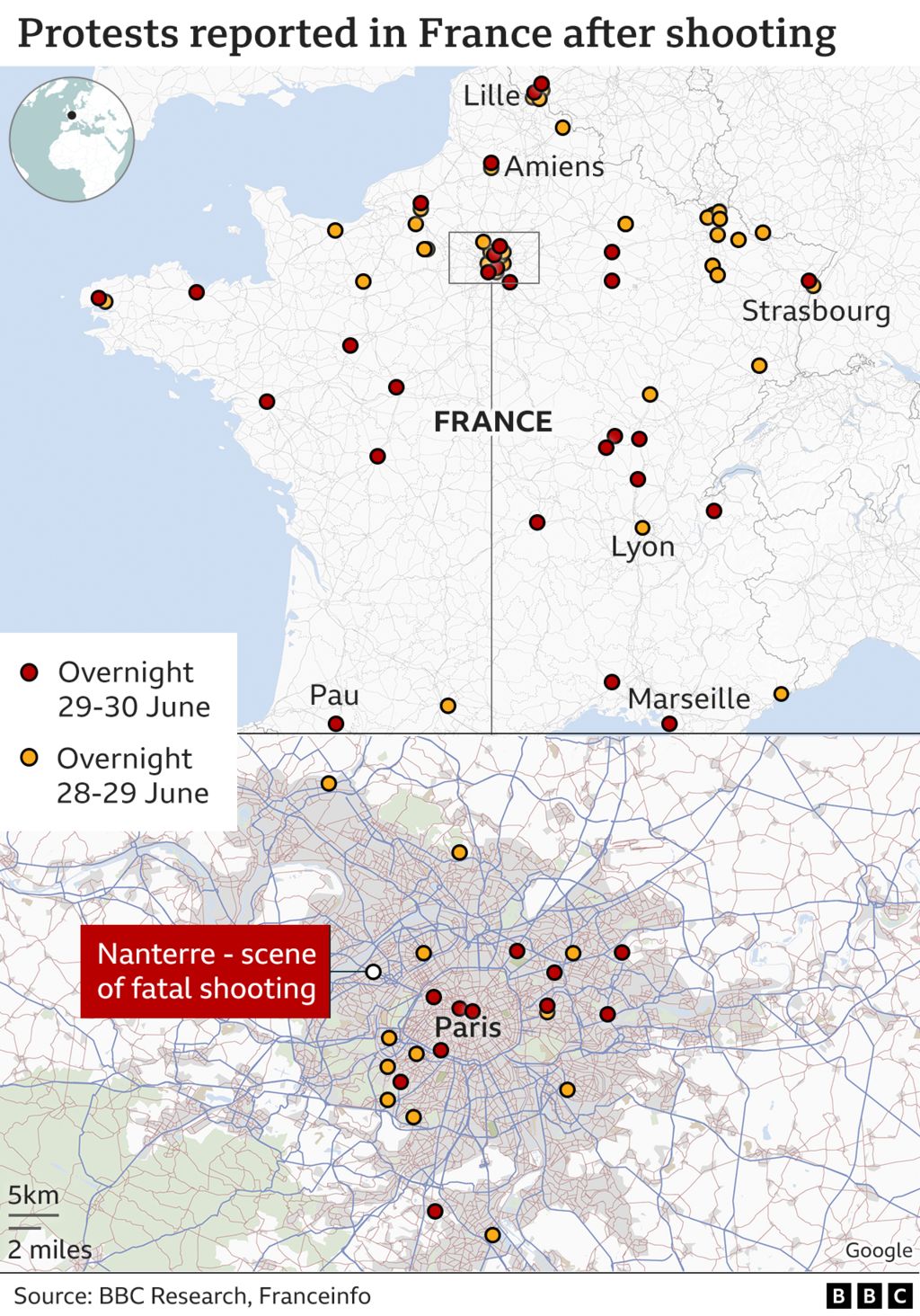

There is no exception with the current firestorm. It began when Nahel M, 17, was killed in Nanterre, close to Paris, after he disobeyed a policeman's order to stop his car.

The tragedy has brought attention back to France's so-called "banlieues," or the suburbs of French cities, which have recently experienced another round of riots.

Some believe that poverty and discrimination are to blame for the violence because these social problems keep France's depressing estates tinderboxes.

Others see the unrest as primarily a law-and-order problem: gangs and small-time criminals using a tragic death as an justification to cause mayhem.

The authorities have long been aware of the problems in France's banlieues, and they won't be solved any time soon, regardless of how you choose to view them.

The first plan to revitalize housing estates was introduced in 1977 by the then-prime minister Raymond Barre, who was worried that they might turn into "ghettos.".

In order to close the gap with other regions of the country, a "politique de la ville" (policy for the city) has evolved over time, encompassing everything from housing to education, employment, health, and culture. .

The National Council for Cities, the Inter-ministerial Commission for Cities of Urban Social Development, and the National Agency for Urban Renewal are just a few of the numerous government organizations that have been established. Additionally, a plethora of initiatives have been given acronyms, including FNRU (Nation Programme for Urban Renovation) and ZUS (Sensitive Urban Zones).

More than €60 billion (£50 billion) has been spent in the past 20 years on a massive effort to build new homes and renovate existing apartment buildings in the banlieues.

However, the outcomes of such government activism don't seem particularly impressive.

More than five million people live in the most impoverished areas, now known as "quartiers prioritaires.". Many are either third or fourth generation French or immigrants.

In comparison to the country of France as a whole, where the poverty rate is 21%, those communities have about 57 percent of children living in poverty.

Residents of these quartiers are three times more likely to be unemployed, claims the think tank Institut Montaigne.

Isolation remains one of the main complaints residents make, despite the fact that billions of euros have been spent to improve transportation.

New public structures have risen. However, public service cuts, according to French sociologist Christian Mouhanna, have had a disastrous impact.

Even school isn't seen as a way to better these people's lives, he told the BBC. According to Mr. Mouhanna, discrimination, drug use, and unemployment all persist unabatedly.

Police relations are yet another significant issue. Many men of immigrant origin claim that officers have discriminated against or race-profiled them.

The latest unrest presented France with an opportunity to "address fundamental issues of racism in law enforcement," according to the UN's human rights office.

Others draw attention to the difficulties in policing high-crime areas. A total of 36 security force members lost their lives while performing their duties in France between 2012 and 2020. Every year, at least 5,000 people are hurt. The total for the year will be significantly higher given the hundreds of officers injured in the most recent disturbances.

The death of Nahel M wasn't an unusual occurrence. 13 people were fatally shot by police last year for disobeying a traffic stop order, according to police statistics.

A depressing cycle is fueled by long-standing tensions: every death sets off a violent outburst, and the police's necessary response only serves to foster mistrust.

The first banlieue riots took place in Vaulx-en-Velin, a destitute Lyon suburb, in 1979 when a teenager slit his veins following an arrest for car theft. Two years later, a second attempt to solve a car theft led to days of unrest in the neighboring town of Vénissieux.

Similar issues occurred in 1990 and 1993 as a result of the deaths of two teenagers in the same neighborhood.

2005 saw by far the worst unrest. While evading police, two teenagers perished in an electrical substation close to Paris. Suburbs erupted all over the nation. A three-week state of emergency was induced by the burning of cars, the robbing of stores, and the assault on police.

There have been sporadic outbreaks in the banlieues ever since. Town halls, police stations, schools, and other structures connected to the French state are frequently targeted, as has been the case recently.

It might be tempting to draw the conclusion that efforts to integrate the suburbs into society and the economy have been a costly, multidecade failure.

There are numerous complaints about missed deadlines and inconsistencies when looking for news articles about "politique de la ville" (this reporter is aware because he has written one).

The Court of Accounts, France's official auditing body, noted in 2020 that despite an estimated €10 billion in annual government spending on banlieues, these areas continue to be plagued by poverty, insecurity, and a lack of services.

However, this does not imply that the spending was in vain or that the policies were unsuccessful. .

The situation is still very bleak when you consider the banlieues as actual places. But there might be cause for optimism if you concentrate on the people.

The "quartiers prioritaires" are areas with a lot of relocating residents. According to a 2017 official report, 10–12% of locals leave the area every year, usually moving to a nicer suburb.

This means that, at any given time, a banlieue's inhabitants have an average tenure of less than ten years of about two-thirds. Overall, the populations continue to be alarmingly underprivileged, but the underprivileged of today may not be the underprivileged of tomorrow.

Stars like actor Omar Sy or footballer Kylian Mpappé are the media-friendly representations of success in the banlieue. The fact that many of their childhood friends are probably currently working as software engineers or shop managers, however, is much more significant. .

The social mobility of immigrant descendants has recently been highlighted by France's statistical body, Insee. According to its report, the percentage of university graduates among them is comparable to that of the general population.

Compared to their native counterparts, foreign-born French people with an unskilled father are more likely to hold managerial positions—33% as opposed to 27%.

Of course, discrimination, a lack of opportunities, and other issues still affect immigrants and their offspring. The fact that many people leave the banlieues is of no consolation to those who have lived there for a long time.

These people will still experience disproportionately high rates of poverty, unemployment, and violence. They will encounter law enforcement two to three times more frequently than other French people. They can only hope to escape before the upcoming riot wave.