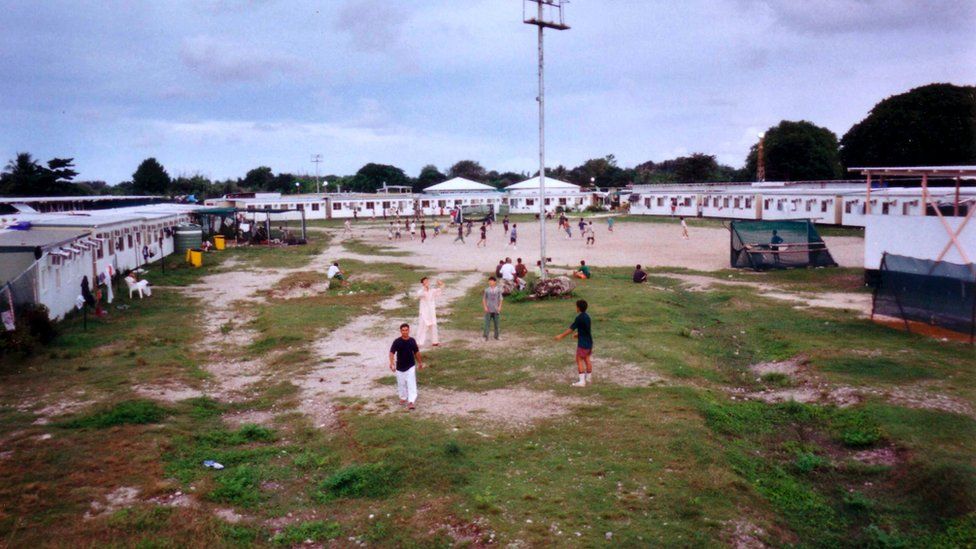

After the final refugee was evacuated into the night last week, Australia's contentious detention facility on Nauru is now empty.

There have been 4,183 people detained there since 2012, pausing Australia's processing of asylum seekers on the small Pacific nation for more than ten years.

The Nauru center is a sore spot on Australia's human rights record; visitors from Doctors Without Borders and Human Rights Watch described it as a place of "indefinite despair" and "sustained abuse.".

However, one of Australia's longest-lasting policies is offshore processing, which involves holding people in the Pacific while they wait to be resettled in a different nation.

Its importance in defending the country's borders and "breaking the business model" of human traffickers has been argued for by seven successive prime ministers.

The government of Prime Minister Anthony Albanese will spend enormous sums of money, including A$486 million (£255 million; $320 million) this year, to keep Nauru open as a deterrent even though the facility is vacant.

Maria has experienced being abruptly airlifted off of Nauru. After being imprisoned on the island for more than a year, she was evacuated to Sydney in 2014 due to a serious kidney problem.

Maria, a Somalian who had survived female genital mutilation, fled civil war and traveled to Australia over the course of several weeks by plane and boat.

As she left the house for the last time, her younger brother had begged her, "Just promise me: don't die.". .

Maria, who doesn't want to use her last name, says, "That broke me because we have lots of neighbors and cousins who have died in the Mediterranean.

Maria tells the BBC that her time at sea felt like it would never end. There was no bathroom on board, and the boat was small—"like a kayak.". "I was so ill that I was having hallucinations. I couldn't stop considering my brother. How I wished I hadn't wanted to mislead him. " .

They were eventually rescued by the Australian Navy and transported to Nauru.

Maria has vivid, intense memories of the island. She describes walking on sharp stones in the sweltering heat with her feet cut up and burned. She continues, "green and black mould which grew on everything" covered her tent as a result of the humidity.

She picked up group movement and the importance of ignoring sexual advances from campers in public. According to Maria, "dehumanizing" treatment such as being watched in the shower or having sanitary pads rationed out became the norm. .

"The guards and the girls engaged in a lot of improper relationships. Despite the fact that you are a refugee, they treated you like you were a prisoner. ".

Maria was detained in Sydney following her departure from Nauru before being eventually released on a bridging visa. In Brisbane, where she currently resides with her Australian husband and two kids, she runs a business.

However, she must renew her visa every six months, and she constantly fears that she'll be taken from her family and put back in detention. It is in limbo. I have no idea what will occur tomorrow. ".

Since offshore processing started in 2001, numerous refugees have shared accounts of suffering similar to Maria's.

John Howard, a conservative prime minister, introduced it. The policy was put on hold by Kevin Rudd's Labor administration when he left office in 2007 before being reinstated in 2012, also under Labor, initially as a stopgap measure in response to an increase in boat crossings.

The policy has been defended by several politicians as essential to safeguarding Australia's borders and saving mariners' lives.

However, researchers contend that it did little to reduce deaths or arrivals at sea. Both decreased beginning in 2014, when the government covertly switched to a policy known as "boat turnbacks," which involves removing migrant boats from Australian waters and sending those on board back to their countries of origin.

After that pivot, there were no more new arrivals at the offshore detention facilities in Papua New Guinea (PNG) on Manus Island and Nauru. .

And since then, according to a 2021 analysis of offshore detention by the Kaldor Centre for International Refugee Law, "Australia has spent considerable effort and money trying to extract itself from its arrangements in Nauru and PNG.".

Australia evacuated residents from the islands under a unique legislative plan in response to growing allegations that detainees were suffering from health crises.

As a result, everyone has been removed from Nauru, but, according to the Human Rights Law Centre, 80 former government detainees are still "trapped" there.

Every expert UN body tasked with reviewing offshore processing over the past ten years has voiced objections to the practice. Inmates have committed suicide in about half of the fourteen fatalities.

The International Criminal Court (ICC) declared Australia's policies to be illegal and degrading in 2020, but concluded that no charges should be brought against the country.

Despite subtly moving away from offshore processing, Australia recently agreed to pay a US prison company A$422 million to manage Nauru through at least 2025.

According to a Department of Home Affairs spokesperson, "the enduring capability ensures that regional processing arrangements remain ready to receive and process any new unauthorised maritime arrivals, future-proofing Australia's response to maritime people smuggling.".

Regarding the last prisoner leaving Nauru, Mr. Albanese has not made any remarks. His administration's asylum seeker policies have been characterized as "tough on borders, not weak on humanity.".

Offshore processing will continue to be an expensive, bicameral policy, according to critics, as long as "refugees are being used to try and win votes.".

According to Jana Favero, director of advocacy at the Asylum Seeker Resource Center, "people seeking asylum by sea have been weaponized and politicized over decades in Australia.".

However, Ms. Favero and other detractors think that attitudes toward "deterrence-based" border control are changing. She applauds the final exodus from Nauru, calling it a "long overdue move for refugees" that resulted from "tireless advocacy.".

The rejection of fear-based politics was evident in the most recent election, she claims.

According to polling, attitudes toward immigration have changed. According to the Lowy Institute think tank, in 2017 when asked if refugees from Nauru and PNG should be allowed to settle in Australia, 45% agreed and 48% disagreed. This year, its polling revealed that, up 15 points from 2018, 68 percent of respondents agreed that "openness to people from all over the world is essential to who we are as a nation.".

Because so little has changed over time, Maria, who has found herself in the government's crosshairs, says life right now is about learning to live with uncertainty.

It's been ten years already; at this point, she claims to be accustomed to it.

"I try to fully live my life. But on occasion, I feel overburdened and ask, "Why me? "