Solar panels only have a lifespan of up to 25 years, despite being widely advertised as a vital tool in cutting carbon emissions.

Millions of panels will eventually need to be discarded and replaced, according to experts.

More than one terawatt of solar capacity has been installed worldwide. Since typical solar panels have a 400W output, there may be up to 2.5 billion solar panels worldwide if you include solar farms and rooftop installations. ", claims Dr. Rong Deng, a solar panel recycling specialist at the Australian University of New South Wales.

There are tens of millions of solar panels in the UK, according to the British government. But there is a lack of specialized infrastructure for their recycling and disposal.

To avert a looming environmental catastrophe on a global scale, energy experts are urging urgent government action.

According to Ute Collier, deputy director of the International Renewable Energy Agency, "it will be a waste mountain by 2050 unless we get recycling chains going now.".

We're making more solar panels, which is great, but how will we dispose of the waste?, she asks.

At the end of June, when the world's first factory devoted to completely recycling solar panels opens in France, it is hoped that a significant step will be taken.

The facility is located in Grenoble, a city in the French Alps. ROSI, the company that owns it, hopes to eventually be able to extract and reuse 99 percent of a unit's components.

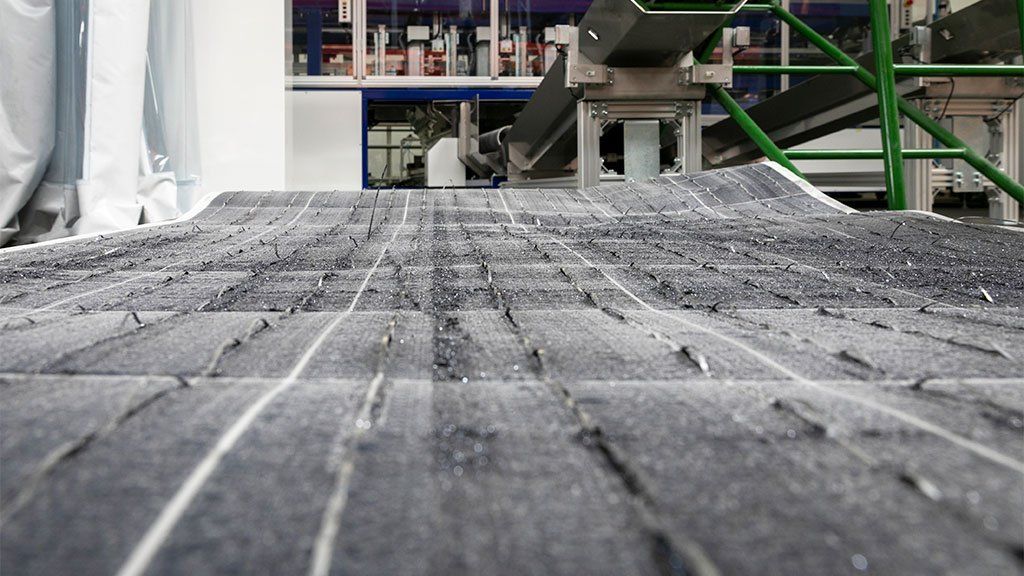

The new factory can recycle the panels' glass fronts and aluminum frames in addition to recovering almost all of the panels' precious materials, including copper and silver, two of the most challenging to extract metals.

After that, these rare materials can be recycled and used to create new, more potent solar panels.

The majority of the aluminum and glass from solar panels recycled using traditional methods are recovered, but according to ROSI, the glass is of relatively poor quality.

The glass recovered using those techniques can be used to make tiles or for sandblasting and can also be combined with other materials to make asphalt, but it cannot be used in processes that call for high-grade glass, such as the creation of new solar panels. .

The new ROSI facility will open at a time when solar panel installations are in high demand.

In 2021, the capacity of solar energy generation increased by 22% globally. The majority of the 13,000 photovoltaic (PV) solar panels that are installed each month in the UK are on the roofs of private homes.

Before they reach the end of their anticipated lifespan, solar units frequently become relatively uneconomical. The development of new, more effective designs occurs frequently, making it possible to replace solar panels that are only 10 or 15 years old with more recent models at a lower cost.

The amount of scrap solar panels could be enormous, according to Ms. Collier, if current growth trends continue.

"By 2030, we anticipate having four million tonnes of scrap, which is still manageable, but by 2050, we may have 200 million tonnes or more worldwide. ".

400 million tonnes of plastic are currently produced globally each year to put that into perspective.

The lack of waste to process and reuse until recently is the reason there are so few facilities for recycling solar panels.

It is only now reaching the end of its useful life for the first generation of domestic solar panels. Experts advise taking immediate action as those units are currently nearing retirement.

The time to consider this is now, Ms. Collier says.

According to Nicolas Defrenne, France is already a pioneer in Europe when it comes to the treatment of photovoltaic waste. The decommissioning of solar panels across France is coordinated by his organization, Soren, in collaboration with ROSI and other businesses.

Mr. Defrenne recalls, "The biggest one [we decommissioned] took three months.".

His Soren team has been experimenting with various recycling methods: "We're throwing everything at the wall and seeing what sticks," he said. ".

The solar panels are painstakingly disassembled at ROSI's cutting-edge facility in Grenoble in order to recover the valuable materials contained therein, such as copper, silicon, and silver.

Only minuscule fragments of these priceless materials are present in each solar panel, and because they are so tightly bound to other parts, it has not been practical to separate them on an economic basis in the past.

But because they are so valuable, efficiently extracting those priceless materials could be a game-changer, according to Mr. Defrenne.

According to him, 3 percent of the weight of the solar panels contains more than 60% of the value.

The Soren team is optimistic that, in the future, nearly three-quarters of the materials required to make new solar panels—including silver—can be recovered from retired PV units and recycled, which would help hasten the production of new panels.

According to Mr. Defrenne: "You can see where you have a production bottleneck, it's silver. Right now, there isn't enough silver available to make the millions of solar panels that will be needed in the switch from fossil fuels. " .

In the interim, British scientists have been working to create technology similar to ROSI.

Researchers at the University of Leicester revealed last year that they had figured out how to remove silver from PV units using a type of saline.

But as of now, ROSI is the only business in its industry to have expanded to an industrial scale.

Furthermore, the technology is pricy. Solar panel producers or importers in Europe are in charge of getting rid of them when they become obsolete. Many people prefer crushing or shredding the waste because it is much less expensive.

Solar panel recycling is still in its infancy, according to Mr. Defrenne. Just under 4,000 tonnes of French solar panels were recycled by Soren and its partners in 2017.

However, much more could be accomplished. And he has decided to make that his goal.

"The weight of all the new solar panels sold in France last year was 232,000 tonnes, so that's how much I'll need to collect every year when they wear out in 20 years. .

"My personal objective is to make sure France is the world leader in technology when that happens. ".

The Climate Question is available on BBC Sounds.