The family of the first patient to receive penicillin treatment is hoping that the success of their relative will motivate pharmaceutical companies to create new, life-saving antibiotics.

Albert Alexander, a Woodley, Berkshire native, received penicillin treatment in Oxford in 1941, demonstrating the antibiotic's positive effects.

He suffered an injury while working as a policeman in World War Two.

His 89-year-old daughter will share her ancestor's tale with antibiotic experts at a conference in Glasgow.

On Monday, Sheila LeBlanc will attend the World Congress of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology in the Scottish city along with Mr. Alexander's two granddaughters.

They traveled from Redlands, California, where they were born and raised, to participate in the activity.

The incident follows earlier research that more than 1.2 million people died globally in 2019 from infections brought on by bacteria resistant to antibiotics, according to research published in 2022.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a "hidden pandemic" that, if antibiotics are not used responsibly, could spread in the wake of Covid-19, UK health officials previously warned.

The problem needed to be addressed, according to Mr. Alexander's family, and people were "taking antibiotics for granted.".

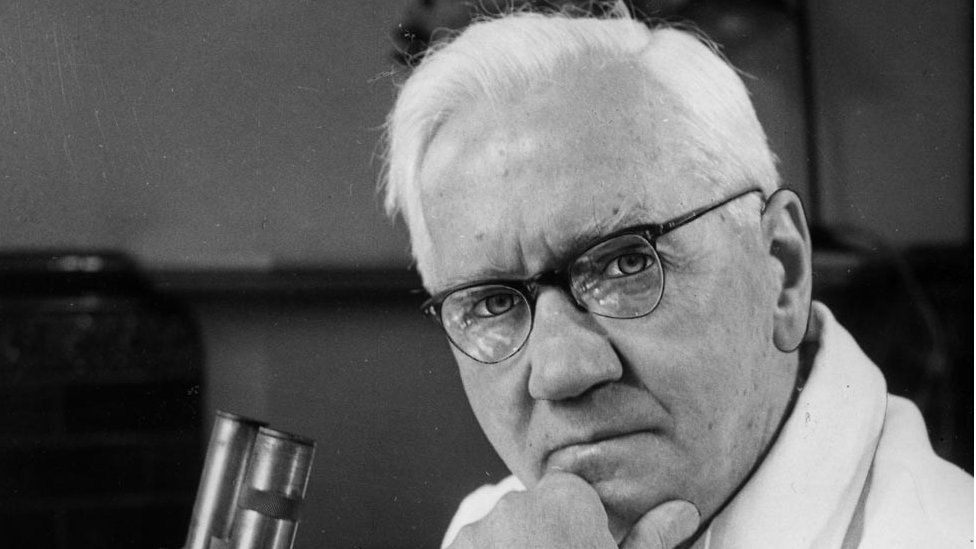

Penicillin was discovered in 1928 by Sir Alexander Fleming at St. Mary's Hospital in London, but it wasn't until scientists in Oxford turned it into a usable medication.

Police officer Mr. Alexander suffered blood poisoning while on duty after being hurt in an air raid in Southampton.

He was taken to Oxford's Radcliffe Infirmary, where he received the recently discovered antibiotic and began to recover right away.

He passed away on March 15, 1941, because penicillin could not be isolated in time to finish the treatment.

However, the incident demonstrated that penicillin was effective in treating human injuries, and in the years that followed, the antibiotic helped many more combat casualties.

Timing, according to Professor Michael Barrett, a microbiologist at the University of Glasgow, was crucial when examining penicillin's role in the war.

"We probably cut a year off the Second World War," he continued, "by having Albert there in that condition to treat at that time and to demonstrate the potential to work. ".

However, according to Professor Barrett, there is currently insufficient funding for the development of new antibiotics, and he has cautioned that this could create a crisis.

At the Glasgow conference, he will attend with Mr. Alexander's family.