We are frequently informed that a technological revolution is currently taking place.

Computers, the internet, faster communication, data processing, robotics, and now artificial intelligence are all transforming and improving business and the workplace.

The only minor issue with this is that none of it appears in the economic data. There is very little proof that our ability to work faster and more effectively is being facilitated by technology.

The UK's productivity, or the amount of output produced per worker, increased at a rate of 2.3 percent per year between 1974 and 2008. However, the rate of productivity growth fell to roughly 0.5% per year between 2008 and 2020.

Additionally, productivity in the UK fell 0 point 6 percent in the first three months of this year compared to the same period last year.

In most other Western countries, the situation is similar. Between 1995 and 2005, productivity growth in the US was 31%, but from 2005 to 2019, it decreased to 14%.

Although it seems like we are still in the midst of a significant period of technological innovation, productivity has slowed to a standstill. How would you resolve this apparent contradiction?

It's possible that everyone is just using technology to put off doing work. For instance, sending endless Whatsapp messages to friends, binge-watching YouTube videos, yelling at people on Twitter, or just mindlessly browsing the internet.

Or, of course, there may be more significant underlying factors.

Economists take a very close look at productivity. There are two main theories as to why technology is not increasing productivity, despite the fact that it is a complex issue with the effects of the 2008 financial crisis and the current high inflation rate.

The first is that we simply aren't accurately measuring how technology affects society. The second is that economic revolutions typically take a while to get going. Therefore, technological change is occurring, but it could be years before we fully reap its rewards.

Dame Diane Coyle is a renowned authority on productivity measurement and the Bennett Professor of Public Policy at the University of Cambridge.

"Today, everything is digital, but it can be challenging to understand what is happening because none of this is reflected in the statistics. Simply put, we don't gather the data in ways that would enable us to better comprehend what is going on. " .

For instance, a business that once spent money on its own computer servers and IT team may now outsource both to an international, cloud-based provider.

The outsourcing company receives the best software that is consistently updated, trustworthy, and reasonably priced.

However, this effective move makes the company appear smaller rather than larger when viewed in terms of how we gauge the size of the economy. Additionally, it is no longer perceived as making investments in that portion of its IT infrastructure, which was previously counted as part of its economic growth. .

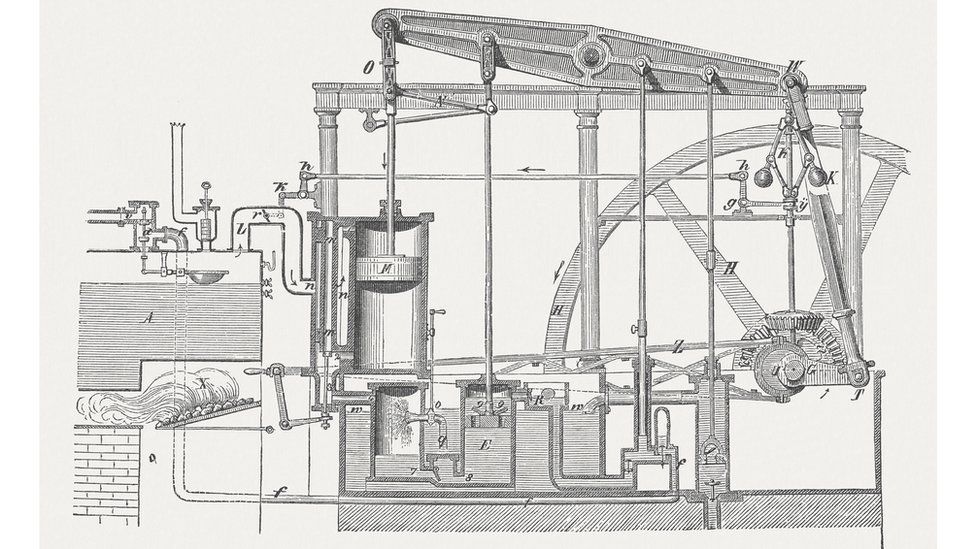

Dame Coyle uses the industrial revolution of the 19th century as an example to show how statistics can miss productivity.

There are 120 pages in her 120-page 1885 yearbook of statistics for the UK, almost all of which are devoted to agriculture. There are also 12 pages devoted to mines, railroads, and cotton mills.

At the height of the industrial revolution, during the era of the so-called "dark satanic mills," 90% of the information collected was about an aging, steadily declining sector of the economy, and only 10% was about what we now recognize as one of the most significant economic shifts in human history.

According to Dame Coyle, "We see the economy through the lens of how it used to be in the past, not how it is today.".

The series "New Tech Economy" examines how technological advancement is expected to influence the new, emerging economic landscape.

The alternative claim is that the current technological revolution is actually occurring, it is just happening more slowly than we anticipate.

Professor emeritus of economic history at the University of Sussex Business School is Nick Crafts. He makes the point that the significant shifts in economic performance that we typically perceive to have occurred almost instantly actually took decades, and that this may be the case again.

He states, "James Watt's steam engine was patented in 1769. "However, the Liverpool to Manchester line, the first significant commercial railroad, didn't begin operations until 1830, and the main railroad infrastructure wasn't completed until 1850. It had been 80 years since the patent. ".

The same pattern can be seen in how electricity is used. The light bulb was first used in public by Edison in 1879, and it took at least 40 years for entire nations to be electrified and steam power to be phased out of manufacturing.

In fact, it's possible that the world is currently experiencing a similar pause, similar to the period between the world's peak use of steam power and the full development of electricity. .

However, the nation and the companies that can utilize new technology the best and quickest will prevail in the race for productivity. This seems to depend less on the technology itself than on how well you can use it, adapt it, and exploit it—in other words, how skilled you are—much like it did with steam and electricity.

Dame Coyle already foresees this happening. There is a lot of evidence showing that, regardless of the type of business, there is a growing gap between those who can effectively use technology and those who can't.

If you have highly skilled workers, a ton of data, know how to use sophisticated software, and can change your processes so that people can use the information, it seems that your productivity will soar.

But other businesses in the same economic sector simply are unable to do that. " .

In some ways, technology is neither the problem nor the solution, despite appearances to the contrary. Only those who learn the best ways to use it will experience high productivity growth.